We introduced the statistics, the almost impossible feat and the question in our first article in the series, which can be found here:

https://www.ijf.org/news/show/151-olympic-champions-tokyo-to-tokyo

A reminder of the question:

It could be said that to be in the company of an Olympic judo champion is to be presented with someone who has reached an absolute pinnacle, a ceiling which cannot be surpassed; there is nowhere further to ascend in the world of sport. We often find Olympic champions speaking with freedom and certainty, unafraid to share an opinion, speaking of their lives and journeys with confidence. For many we feel there is peace, and that can be magnetic and inspiring.

So the question is, did they become Olympic champion because of that character or did they become that person having won the Olympic gold medal?

“It comes from myself, from my character. I didn’t change after becoming Olympic champion. I am discreet and determined, someone who has his own values and defends them, like justice, freedom and transparency. These strands are for all of my life, not just from 1992 or a gold medal. Sports-wise, it’s something that makes me want to contribute to sport and develop sport to ensure fairness. This is in my character.

For any given athlete who became Olympic champion, there’s a reason. My path was built through the whole cycle and also my whole life. I started at 4 years old and had a very good and close coach who guided me. It was important to develop at that early age. My practice and involvement with judo were connected simultaneously with my development as a child, as a person; judo and life were interconnected from the beginning. Lessons from judo fed my life. Brazil has the largest population of Japanese origin outside Japan and so Japanese culture and history are present in our society. Judo is big in our country and in judo we follow a Japanese mentality.

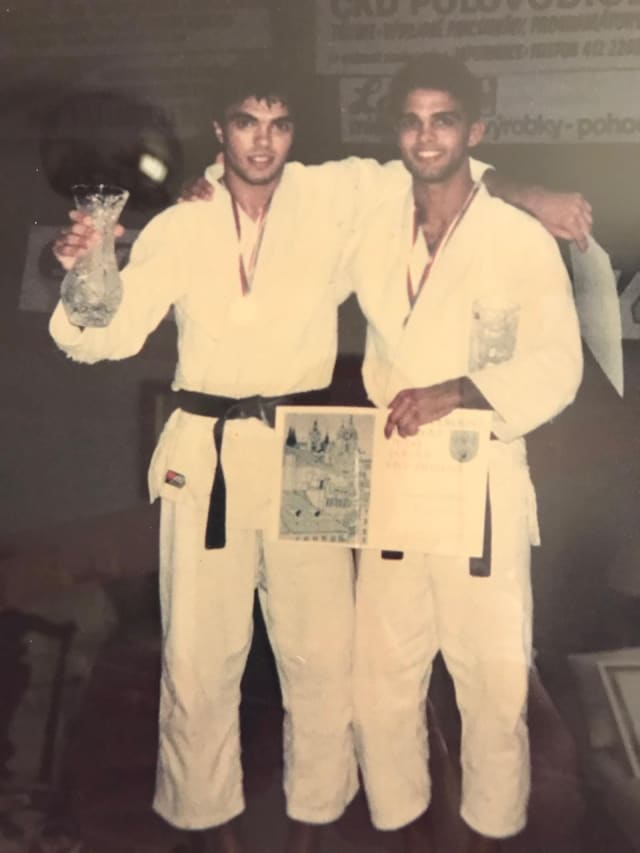

In 1988 I began with the Brazilian national senior team. I went to big, important events such as the opens in Prague, Budapest and Germany, all before the 1988 Seoul Olympic Games. I fought for medals at all of them, some won and some lost, but I didn’t make the Olympic team that time. I was beaten by my brother who went to Seoul in the same weight, Ricardo Sampaio.

Just after Seoul, Ricardo retired as there wasn’t so much investment in sport in Brazil. I then stepped up to occupy the Sampaio weight category, -65 kg, and I became the number one for Brazil. Then I started to prepare for the ’89 worlds; in those days it was every two years. Ten days before that worlds in Zagreb, the whole Brazilian national team started a movement against the leaders of the federation, to fight for better conditions, for investment, fairness and subsidies.

Just for the record, we used to train in very poor quality dojos, straw floors with some kind of covering. We usually paid with our own resources. We had no professional support such as physiotherapists or nutritionists, among many other problems.

Ten days before that worlds, the whole Brazilian team pulled out and did not compete. At that point, I believed I was in the top 5 in the weight in the world. After that movement to step out of the worlds, as a protest against the federation, initially we thought it would be a fast resolution, but it turned out that we were out of the national team from October 1989 to January 1992. As we were not welcome with the federation, we were kept away from all international competition for two years and three months. It’s a bitter sweet feeling because on one hand I was upset to not be able to compete, due to this punishment, but on the other hand I feel very proud to have been among the leaders of a movement that wasn’t aiming at personal achievements, acting for the benefit of all of the Brazilian judo community.

At the same time, during that two year span, there was another tough situation as in 1991 my brother Ricardo took his own life. This personal loss was very difficult for me and my whole family. It’s something that was not talked about at all back then but nowadays I see it is a big deal for all Olympic committees, to support career transitions. Retirement causes many athletes a great deal of pain.

All in all, in January 1992, the same athletes who carried the movement against the federation finally made an agreement to come back. The federal government intervened to support both the federation and the athletes; it was a big sport in the country and everyone wanted a solution. It was an important protest and in important solution because after that period the athletes had more voice and power; there was a better environment for judoka in Brazil, with more attention from the federation.

My main concern then was that once I was cleared to fight again, I had to regain my best shape, the right rhythm and competitive feeling, all in time for the Olympic Games. I had to put all my effort into gaining my best condition. I had to make my way back to that top 5 position I was once in. For 6 months, on the way to the Olympic Games, I tried to practise as much as I could. We had a Japanese style of training that was very hard, very rough. I didn’t have a personal coach at that time either. Me and my coach Paolu Duarte were together for very many years but we parted ways in a friendly way in 1989 and I didn’t take another coach.

In the final lead up to the Olympics I started to be more and more strong; I developed my own route to the Games. I consider myself a judoka with a versatile and dangerous style. I had good technique and could score from many places. It was a different judo from today’s though. I used a lot of movement and had a broad range of techniques. I was left-handed but was able to work everywhere; I was always looking for ippon. I was away from the circuit for a long time but it ended up helping me as I was off the radar. Many opponents in Barcelona didn’t know me or knew me from a different time; I was an underdog!

At the Olympic Games, I knew I could be a surprise and make a great run but at the same time I knew I had to go step by step and fight by fight, not rushing too much. I won my first three fights in Barcelona quite fast and preserved some energy for the semi-final and final. The most difficult point was the break between the preliminaries and the final block. You start to think too much and about winning a medal. It’s a dangerous time full of overthinking. I started to think about how I could prepare to do what I wanted to do. There was so much at stake. At that time we didn’t have psychologists to assist, we were pretty much on our own. The way I carried myself through from my childhood, the protest, my brother and my Japanese way of fighting and thinking, all helped me to be tough and come into the final block feeling strong. In the semi-final I faced a tough opponent, Udo Quellmalz. Udo was the number one and I consider he was maybe a better judoka than me. I thought I could beat him though, I believed in myself. It was the most difficult fight of my life and I remember being so tired, like it was hard to breathe and my eyes were super wide. I kept saying to myself, ‘If I am tired then he must be tired too.’ I saw his wide eyes and decided he was tired so I knew, in my mind, I could do it.

The final was against a Hungarian and I won that contest too. I had the belief that I was among the best. It didn’t matter what we did before, only what we could bring on the day. A motto from the Brazilian sport director at that time says, ‘We prepare our entire life for a gold medal but can lose it in one day, one decision, so you have to be ready on the day.’ I believe that winning a medal, especially at the Games, is not something that happened on the day with luck, it’s not random. You prepare for it all your life but then have to overcome the obstacles and opponents on the day. I was ready.

I retired in 1998 at 31, which was quite normal. I feel like Ricardo is very present in my life, as is my father, despite him passing 13 years ago too. I catch myself talking with them and reflecting with them even though they are not here physically.

I started judo in 1972 and was scared of it at first and didn’t want to practise. My brother attended just to help me get used to it. Judo was chosen because I had a lot of energy as a young boy. Ricardo didn’t plan to do it but came to show me the way. We had a strong bond and losing him was hard.”

Rogerio Sampaio is an Intelligent rebel who endured a lot of adversity which taught him to cope and so there was a great deal of evidence that he could do it. He had good technical training from a young age and always lived by his values, not just for himself but for the group. All of this contributed to him becoming Olympic champion.

“Now at 57, I work as Director General of the Brazilian Olympic Committee, in role since 2018. I keep that fire inside me, making Brazilian sport better, creating better environments for young athletes and former athletes. I work to provide support for everyone involved.”

Rogerio Sampaio was the Chef de Mission for the Brazilian team at the 2024 Paris Olympic Games.