Today our sport, judo, is celebrated as a model of equality and equity between men and women (same number of weight categories and events, same prize money offered to men as to women), but the road here has not always been easy and women have had to fight for a long time to have their rights recognised. We are talking about a bygone time here. However, on the occasion of the celebration of the first women's world championship, it seemed logical to pay tribute to those women whom have, many times, braved the cold in the face of prohibition and whom often stood up against the established order, in an essentially male sporting world.

In this first article, we will come back to the history of the pioneers. The names of those who contributed to develop judo and that we have sometimes forgotten, must remind us that it is possible to change things, that it is possible to overturn mountains. Some have done it and all current judoka, women and men, can take their hat off to them. In 2021, during the Tokyo Olympic Games, for the first time in history, a mixed team tournament will be held. This is the best tribute that we can pay to the pioneers of world judo.

Women's judo is therefore the result of a long struggle for equal rights, which was far from obvious at the end of the 19th century, when judo was created. As we underlined in the introduction, today the female medal-winning champions are at exact parity with their male counterparts. Their titles are appreciated at their true value and many female champions are the pride of entire countries.

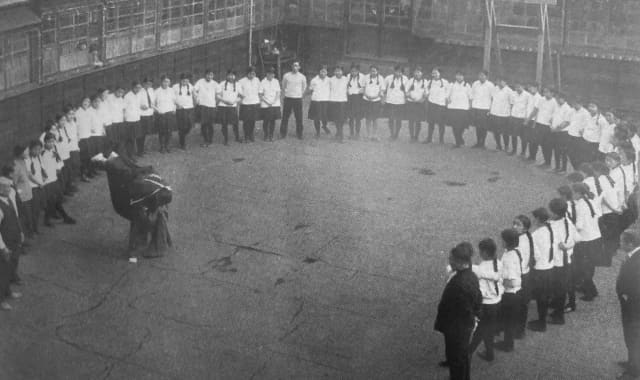

To get there, women have had to overcome many obstacles in a world where male norms and values dominate. Throughout this journey, they were able to assert their rights by dint of self-sacrifice, with the support of their peers but also of men who understood that the man-woman division in sport no longer had its place. At the very beginning of the history of judo, one has to imagine societies dominated by men, whose laws were written and enforced by men. The place occupied by women in combat sports, their attitudes and their behavior were therefore not positively seen and were diminished by the rules and social models in force.

A careful look at the evolution of women's practice allows us to identify two distinct periods. The first extends from the beginning of the 20th century until the 1960s, when only a minor place was given to women. At that time, a woman's freedom of action on a tatami was considerably restricted. During the second phase, from the 1970s to the present day, judo takes on an increasingly marked international dimension, more and more women practising and they demand equality for access to championships, which we can see today, has been a successful campaign.

As we look back at a world moving into the twentieth century, it must be remembered that the practice of sport and physical education was then supposed to make women more beautiful and healthy while preparing them to fulfill their future role as mothers. Many educators agreed that women were not built to fight, but to procreate. At the time attitudes were governed by men and behavior had to be 'appropriate'. Physical exercise for women was precisely defined by medicine, which was opposed to any sporting activity likely to be detrimental to the reproductive function.

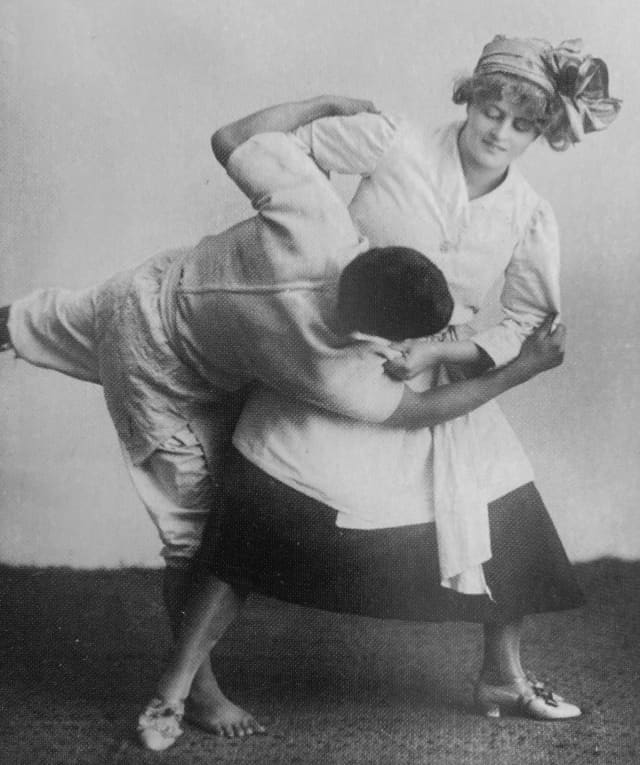

However, while the fighting methods from Japan were on the rise in Europe, a fundamental movement was emerging, which rehabilitated the use of intelligent force, offering prospects to women who asked only for emancipation. Martial arts therefore seemed to appeal to the 'new women' fighting for the recognition of their rights. It should also be emphasised that this period coincided in many countries with the beginnings of the struggle for women's right to vote.

In London for example, 'jujutsusuffragettes', as they were sometimes referred to, were inclined to harness the effectiveness of martial arts and when participating in demonstrations it was not uncommon to see them using combat techniques, like a defensive weapon, to face the police.

Edith Garrud and her husband learned jujutsu from a Japanese master, Uyenishi-sensei. She began by assisting her husband and then in 1909 she opened her own dojo and ran a personal defence club for suffragettes. She trained a group of around thirty women. After raids, some of the students rushed into Mrs. Garrud and hid their signs under the tatami where they trained.

Across the Atlantic, in the United States, the wife of Yamashita-sensei, the expert who gave lessons to President Roosevelt, mustered all her clout and position in order to encourage the participation of American women in what the New York Times called in 1904, 'the madness of Japanese fashion.’ It was not uncommon then to see Yamashita Fude in the company of her husband during self-defence presentations in Washington and quickly the transatlantic press got interested in this new fashion which was developing within high society. Personal defence seemed at this time to be recognised as an implicit right. Yet American activists, like their British colleagues, apparently did not exploit the advantages of Japanese techniques, to change society.

In Japan, where judo was born, the art of combat was then an exclusively male privilege. Nevertheless, as in the West, physical education exercises for women were intended to improve grace and health.

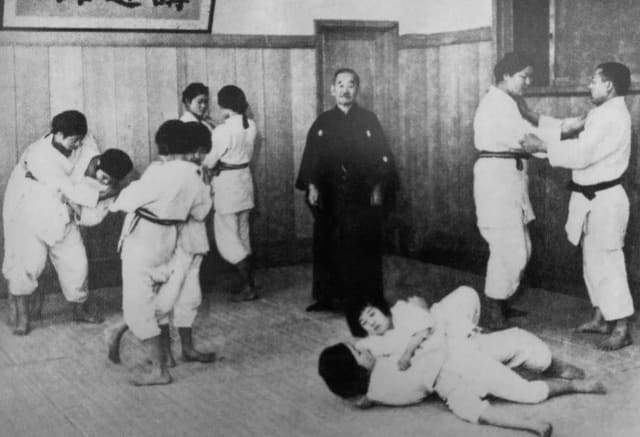

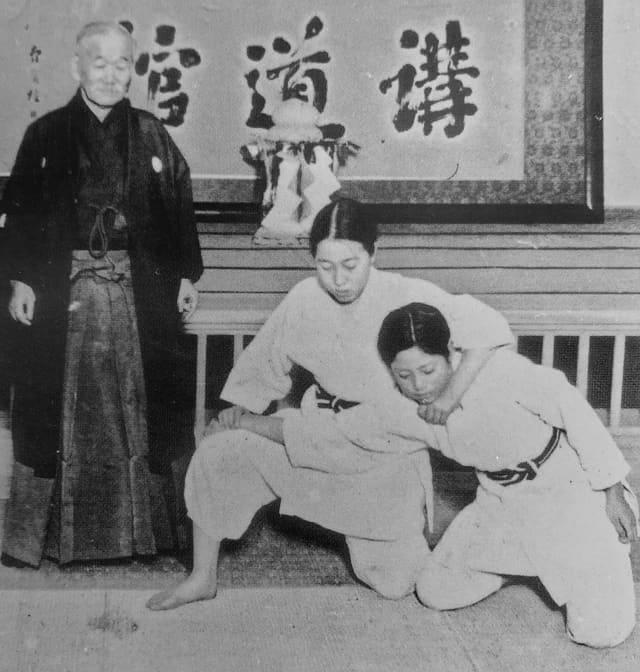

Kano Jigoro Shihan, who was a man of his time, adopted the concept of a female body, defined by the scientific and medical theories to which he had access. He therefore adhered to the idea of biological difference and forbade any excessive exertion. Very quickly, however, the Kodokan archives show a first female entry, Miss Ashiya Sueko. As early as 1893, a few years after the advent of judo, Kano was already teaching judo to his wife, Sumako, as well as to her friends. It was not until November 1923 that regular education for women was put in place, though. A summer training schedule was organised in 1926 and then an official programme and dedicated women’s section was created in November of the same year, but women's judo was then limited to physical and moral education. The practice was reduced to the exercise of kata and randori, while competition was forbidden.

In 1933, a dojo was reserved for the female section of the Kodokan. Chief Instructor Uzawa Takashi reported in his inaugural address, “The physical endurance, physiological make-up and psychology of women are different from those of men. As young women are expected to become mothers, the practice of Seiryoku zen'yo kokumin taiiku no kata for improving physical strength and endurance, required for falls and randori, is essential; otherwise they should not do these exercises. I specifically ask female students to train rationally and avoid overeating as physical fatigue leads to injury and illness. The reason women are not allowed to participate in competitions is that it would lead them to over-train and that they would be obsessed with winning. This would put them at great risk of illness or, in the worst case scenario, a bad accident which could have devastating consequences. We are very concerned about these issues."

A year earlier, in 1932, Ms. Ozaki Katsuko had been the first woman to be awarded the rank of black belt, a rank which was confirmed by Kano himself a year later.

As judo grew more and more and was enriched by Kano's theories, it acquired new scientific and educational dimensions, while the founder of judo spared no efforts to internationalise his method. Kano, ahead of his time now, through his incessant travels abroad and thanks to the sending of his main students across the planet, himself organised the spread of women's judo.

In the United States, pioneers became ambassadors of judo. Ruth Horan, then playing in a music group in Greenwich Village, discovered judo in 1951, while watching a famous television programme, the 'Arthur Godfrey Show.’ With her husband, she decided to take lessons. “Unfortunately, there may be times when we are alone and unprotected. Avoiding problems is the best use of judo,” she said. Defence through judo was thus presented as a service to the community.

Women rarely came alone to practice. They were all wives, daughters or sisters of the male judoka. This was how Helen Carollo came to judo, after a public demonstration. In 1941, she joined the Oakland Judo School. In 1953, having obtained her black belt, she went to Japan and she trained for a year in Tokyo. On her return, she was accompanied by a Japanese expert, Kodokan emissary, Fukuda Keiko.

Ms. Fukuda was then the highest ranking woman in the world, being 5th dan. Her role was decisive in the dissemination of the methods and values of Kodokan women's judo. Her motto, “Develop harmoniously your mind and technique" was used in many American dojos.

Fukuda Keiko played a pivotal role in spreading women's judo around the world. Taking her pilgrim's staff, she ran courses in Australia, Canada, across Europe and many other countries, emphasising the teaching of kata and the physical and mental benefits of practising judo. Ninth dan in 2006 by the Kodokan and 10th by the American federation, at the age of 93, as the last surviving student of Kano Jigoro Shihan, she had not forgotten the difficulties she had to overcome in a world of men.

Without these courageous women, women's judo would not be what it is today. The judo community owes them a lot. We will come back soon to the beginnings of women's competition, which will lead us to talk about the first world championships in New York.

Source: Judo for the World by Michel Brousse and Nicolas Messner - IJF July 2015