We do understand in basic terms what it means to control ourselves. Then we learn to analyse more deeply and find a new layer which incorporates forward planning of controlling ourselves and specific training for doing it better. We then think we have mastered it. Then we find there is another layer and we have to re-train ourselves to be so automatic about our skills of self-control that we can no longer plan it, but execute it, within a multitude of environmental variables, without thinking. It becomes part of who we are rather than a distinguishable chapter.

Thus we must, as always, first of all, know what we are talking about. The notion of the moral code of judo, including self-control, must be extended to mastering it, linking to cognitive processes which are not innate, even if they are necessary to regulate one's behavior in order to achieve specific goals. The young child, for example, does not have at birth the self-control required for a life in society, which is respectful of everyone. They will learn it as they go along. Some will be inclined to learn faster than others, it is a fact, but nobody has from birth, the control and even more the mastery of their emotions.

In psychology, specialists sometimes speak of emotional self-regulation. It therefore seems that the functioning of self-control can be compared to a muscle; self-regulation, whether emotional or behavioral, may prove to be a limited resource that functions like energy. In the short term, excessive use of self-control will lead to exhaustion, while in the long term, the use of it may increase and improve over time. These first observations already make it possible to understand the interest of training in judo, which requires developing physical capacities on the one hand and mental capacities on the other hand, capacities which will help to strengthen the self-control of each practitioner.

People who have poor self-control tend to be risk-takers, impulsive and insensitive to others. If, though, humans are blindly influenced by their passions, they also have their own character trait, that of learning to tame their impulses, emotions and behaviors through self-control. Without it, we would be lions in cages, captains without crew, Robinsons lost in the vastness of the ocean, bloodthirsty beasts who follow only their grossest and most belligerent instincts.

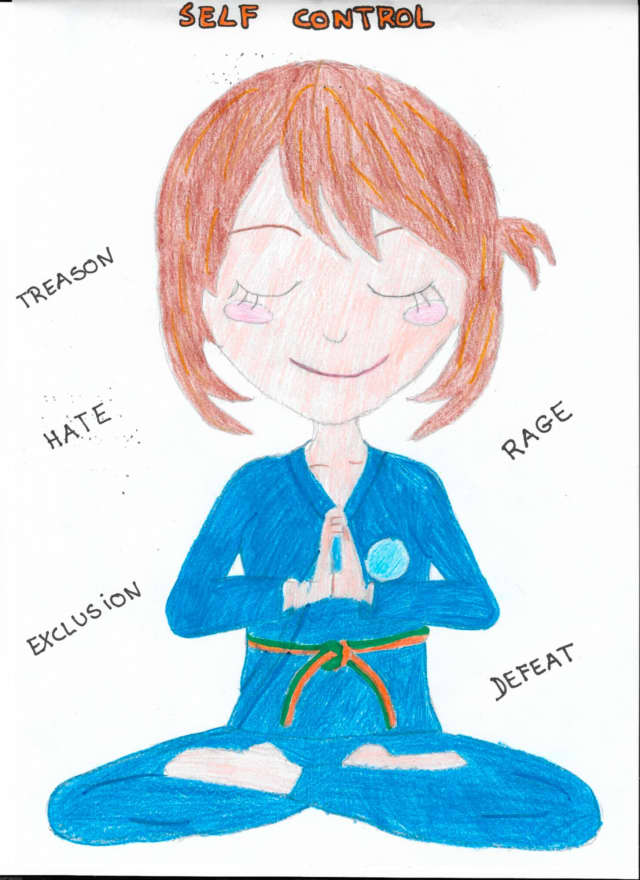

Our ability to not react in a rush and without prior thought is crucial in our daily life, even if the emotions that go through us blind us, letting our demons take over. It is in these cases that socially repressed behaviors can appear, such as anger, violence or even rage. The learning of self-control therefore derives from the assimilation of social limits and the behaviors to be adopted within one's environment.

To develop a balanced psychological life, we need to dedicate ourselves to introspective work. By analysing each compartment of our life, we highlight the areas where our ability to control ourselves is lacking. We can learn and perfect these mechanisms during training or in competition. It would be so easy to unleash destructive emotions, but then the consequences would be immediate: the cessation of all sports activities. Judo and sport more generally, are not circus games. If it is a question of life and death, symbolically, everything stops at that symbolism to allow in our reality only the elements which promote a concerted practice with the others, in an environment chosen and accepted by all.

Regular training and understanding of what makes us learn should allow us to understand what our limits may be. Are we having trouble facing criticism? Are we afraid of failure or rejection? It is by probing our deepest feelings that we will discover the reasons that eventually cause us to lose control. We must be aware of our weaknesses so as not to ignore the real causes of our behavior. It is crucial to identify the triggers so as not to explode when these feelings arise, because knowledge is power. Becoming aware of one's tendency to overreact is already taking the first step towards self-control.

Once we track down the triggers for a lack of self-control, we can focus on them to turn them into a lasting positive disposition. If we know for example that a criticism can drive us mad, it is up to us to manage our anger by means other than confrontation, as with judo.

There will always be situations that will destabilise us. Each time we lose control, unfortunately, we lose both symbolically and philosophically and this defeat is often the antechamber of a defeat on the tatami.

If, on the other hand, we succeed in incorporating the fact that we are better than that, all attempts at destabilisation will only have the effect of demonstrating their puerility. Jealous, envious or unhealthy people, or even destabilising situations, suddenly lose their importance. Through self-control learned and mastered, we have the ability to strengthen our self-confidence. Self-doubt undermines our credibility in the eyes of the world and therefore weakens us.

Ignoring what other people think, not letting anger take over, are the keys to a balanced life. By learning it, we discover who we are and how we can make choices that fulfill us. It is a force, much greater than all anger.

To control our emotions, we learn by practising judo, not to repress what moves us, but on the contrary, we learn to let ourselves be invaded by emotions while preventing them from dictating our behavior. The initial control, which through practice becomes self-control, involves a long process which consists of understanding one's feelings and incorporating them into one's personality to form a whole. For this it takes practice and time

In conclusion, it becomes obvious that the concept of self-control is not easy to grasp and it is important to broaden it to mastering it. This welcomes the emergence of emotions from an initial acceptance. One does not try to control them from a refusal. Self-control is the ability to be fully present in the immediate moment, completely available and open to opportunities and new perspectives. This is what Galileo Galilei did when before the anger of his 'juges' he calmly said "And yet it moves", mastering self-control in the most tense situation and offering a new vision to the world.

Mastering self-control paradoxically amounts to recognising the element of novelty that there is in everything, instead of looking for similarities with a situation already experienced, to try a technique previously known. Mastering is accepting to be surprised by the novelty, to invent a tailor-made response. Mastering a technique means letting go of the result to put all your energy into the execution of the technique. Going even further, mastering the technique is often daring to let go of the technique, to improvise a new response (different from the known technique) to the question posed by the new situation. Where, if not on a tatami, is it possible to learn this permanent, controlled improvisation. When you start a randori, you never know which direction it will go, you never know what awaits you and yet because you have learned to control your emotions, you will be able to make appropriate decisions.

Keeping calm to be lucid, confidence to dare, determination to keep concentration in spite of obstacles and energy to act will guide you on the path of self-control. Cleansed of anger, your emotions will be all the more beautiful.