If you come across Jane Bridge, you might not notice her; petite and discreet. One should not, however, be fooled by appearances because the lady has character and for several decades she has been walking the tatami of the world to share her knowledge and her experience, both of elite level environments and of educational judo and development; a subject that is particularly close to her heart. We interviewed her to tell us about her life as a judoka. Confined at home due to the global pandemic, speaking with her is a true invitation to travel, as she takes you through incredible adventures.

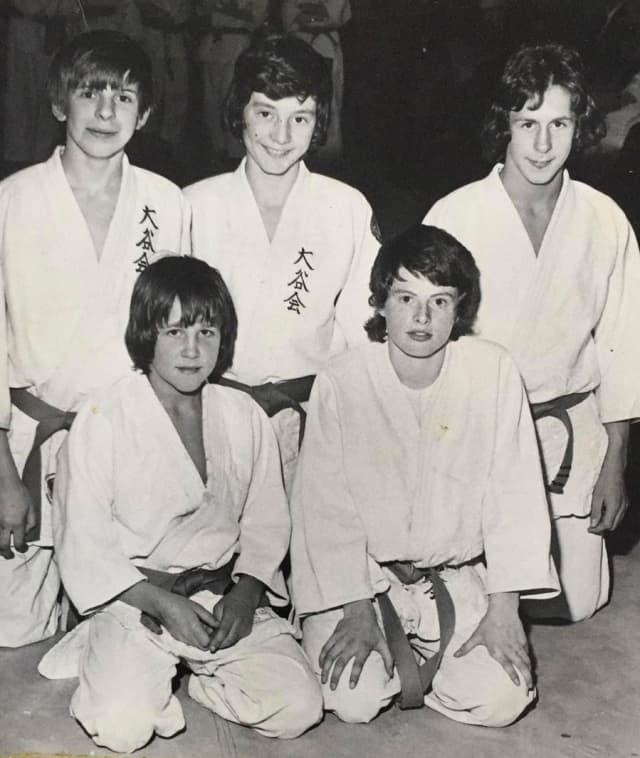

Like many champions, Jane started judo when she was a young child, “I was ten years old. My parents, when they were younger, had done a little judo. That was in another era; no tatami and no teacher either. They were learning from books and trying to replicate the techniques, but they liked it and so it made sense that they put us, my three brothers and me, in judo. My brothers didn't like it, but I did. Then, throughout my career, my parents have continued supported me. They played a big role."

The Bridge family was of humble origin, from Bolton, a town in Greater Manchester, “I lived in a working class environment. When I started judo, I was not licensed to the official federation, but to another smaller organisation. I was able to do a few competitions and I liked it. I practised very instinctively. My first teacher quickly recognised that I had potential, especially under stressful circumstances. We worked a lot on the quality of our techniques."

With this raw potential, at fifteen years old, the decision was taken to register Jane with the official federation so that she could get closer to the national team, "When I arrived for the first time at a national team training session, I was struck by the aggressiveness of the athletes. I did not know it, but, thanks to the judo education I had received, I was technically superior and my teacher was also convinced that one day I would be world champion, even if the event did not exist yet."

A few years passed, during which the budding champion broadened her technical and tactical arsenal. When she finally arrived in New York, at the end of 1980, she had become a big favourite, “It was the first time I landed in the US and the first time I left Europe. It was new and great. I don't remember a lot of things, but I do remember that for my family it meant a lot. My father was a big fan of Frank Sinatra and being in New York was quite symbolic, especially as we were fighting in the very place where Muhammad Ali had become a global star; it was something special. I also remember Mr. Matsumae, then the IJF President, who was traditionally dressed. It was awesome. My parents were there. They had taken out a loan to make the trip."

However, when getting on the tatami, the young woman was not in the best of condition, “It was very strange, because I had contracted a virus some time before, which had left me with half of my face paralysed. We didn't even know if I could compete because I couldn't close one of my eyes. There were risks. I was training with a patch on my face. It took more than six months to get rid of it. If you look carefully at all the pictures from that time, I have a really strange face."

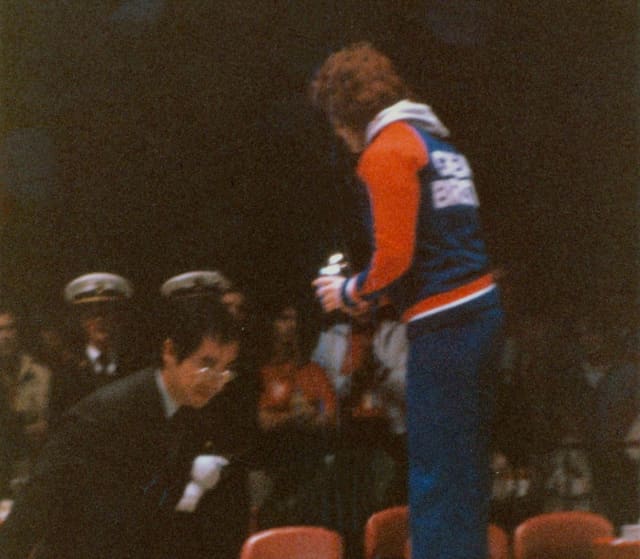

It is obvious now that it didn't stop her from winning, despite the pressure of being the favourite, “Coming in to this first world championship, I was already three times European champion. The British team was very strong. We were even spied on during training, but the day before the competition I broke down in tears. Suddenly, I felt that the step was too high. I really had a lot of pressure on my shoulders. My first fight was difficult. I really needed the mat time to pull myself into the action. I won by a shido or a koka, but little by little I found my rhythm. I remember the final and there is something funny about it.

A year before, in 1979, I spent four months in Japan for training, especially in Tsukuba. A certain Takeuchi Yoshinori was training there and I met him again in the final because he was the referee. He didn't really help me!” Jane laughed. “I scored a waza-ari that I thought was ippon and then I won by immobilisation. After the match, he came to me to tell me that in osaekomi, I should have had my toes hooked into the tatami. It's all in the details."

Becoming a world champion is undoubtedly an extraordinary moment that is difficult to describe and the question often comes up with the new crowned ones: when did you really realise that you are on the top of the world? "Frankly, I didn't really realise. I think I actually only did a relatively short time ago. Back in 1980, when I was in New York, I could see it was a special event, but I was not aware of everything that had happened behind the scenes. I was focused on my competition and I was just happy that I won. Then when I came back to England, being the champion of the world had relatively limited meaning, but gradually, over the years, I realised. Not everyone becomes a world champion. It is reserved for a very small number of athletes, despite the efforts of thousands more. I finally understood long afterwards that it was an achievement and that it marked the beginning of a beautiful future for women's judo and judo in a more global way. Thanks to the organisation and our performances, we put women's judo on the world map. From then on there was no going back possible because even if some did not like it, we had become visible. It's not nothing."

Despite the lack of perspective, the joy of becoming world champion was great, although it was also marred by a certain sadness, “I felt a big disappointment because my training partner lost. It was like I had lost myself. It was Ann Hughes, but she eventually became world champion 4 years later."

Now world champion and a regular atop the European podium, Jane seemed to have achieved everything, “It was not easy after the championships. At the time, I didn’t have the impression that my title really changed the course of my life. For ten years, I was in a period of vagueness. I moved back to live in the North-West of England, but I was lost. I was going from odd job to odd job. One day, I said that was enough. I said stop and I made the decision to leave. It was either for London or for abroad. I finally came to settle in France where I started to teach judo. I started a new life all. These years have been wonderful. To immerse myself in the rich world of French judo was incredible. I could give everything I had learned back to the judo family and build my own family, as well as my professional and personal life. When you look back, you might think that everything was planned, but not at all. You could get the impression that there was some sort of consistency, but above all there was an instinct for survival. I was very lucky to meet wonderful people who have given me a lot and who have allowed me to pass through challenges."

Looking back, Jane Bridge can analyse everything she's been through, with wisdom, “In societies that are drifting more and more towards unhealthy consumerism, I truly believe that judo has an important role to play. It forces us to seek for rightness and it encourages us to help each other and brings us back to basics. We were pioneers in high-level women's sport, but together we can also do so much for communities.

Beyond the title which is and remains important, it is the path that counts. Ultimately the goal is not that important. What is, is what we do to get there. We have to make sure that the trip is rewarding and enriching. This is what we must attach ourselves to in order to pass it on to our children. In my EJU education remit, I try to do everything for judo to be well taught. Principles are important. This is valid for the judo technique as well as for the human approach. Without it everything we do is meaningless."

However, Jane is not fooled. She is proud of her career and measures how much weight her world title gives her, “I want to say that my title weighs the most today. I have real legitimacy to be able to express myself. It's not always easy. When I'm with my partner, sometimes people turn to speak only with him. Then he has to say to them, ‘SHE is the champion.' I believe that it is not the fault of anyone in particular. Society is that way, but little by little things are changing. The lines are moving and once again what we did in 1980 contributes to it. When I see women like Lisa Allan at the IJF or Sanda Corac in Croatia, I tell myself that the fight is worth it. Anyway, I'm not complaining. If people judge by appearances it's their problem, not mine."

The words are strong, the beliefs powerful and Jane's vision for women's judo today is just as direct, “I am very proud to see what women judoka are doing today. They are absolutely amazing, remarkable. When we see a Majlinda Kelmendi, that commands admiration. I can see that there is still a big difference between the best and the others. Sometimes I see attacks on the tatami that are not real ones. I see too much of a tactical approach. I like tactics as well, but the essence of judo is somewhere else. It seems important to me that all the athletes and their coaches understand that they are capable of offering spectacular judo and we have examples of this. They must not accept less."

Jane speaks with the experience of a trailblazer, but also that of someone who had the instinct to survive in a world that struggled with the concept of equality and equity. She can be proud of a journey that is far from over, as she still has so much to pass on. Thank you Sensei Bridge, you are a great judoka and we will continue to follow your lead!