Forty years after the fact, it seems easy to say, yet the obstacles were numerous and it took determination and a lot of self-sacrifice before Jocelyne acquired this stature as a legend of international judo.

It all started with a hyperactive child who, around ten years old, needed to let off steam, “I did a lot of team sports, gymnastics too, but because my father had done judo when he was younger, I ended up on a tatami. It was in June 1965 that my dad took me to see a judo session. I was stuck. A few months later, in September of the same year, I started judo myself, but I was a child in adult circles. I'm sure that's when I started to build a fighter’s character."

By interviewing judoka from all over the world, we discover that there are often points in common between them. It could be the existence of a parental link, with a father or a mother, sometimes both, who already knew judo. Maybe for some there was an early contact with the activity, from childhood, with the hope of channeling the overflowing energy of children. Jocelyne is therefore no exception to this trend. However, from there, to becoming world champion, there is a gap, which can be bridged, but with some difficulty, “Very quickly I found myself doing judo three times a week. I was calmer at school and it didn't take me long to develop a real passion for judo. When I was 17 I started working in a bank, but all my free time was devoted to the sport. In France, women's judo was not very developed yet. It is an understatement to say that. There were no or few competitions, although I could see that in other countries, things were starting to move."

On Saturday afternoons, Jocelyne was on the tatami. She participated in technical courses for women. One of her friends told her about her fiancé, a certain Jean-Luc, “It wasn't until 1975, when he became the first French world champion, that I discovered that this Jean-Luc was none other than Jean-Luc Rougé. I could not yet imagine that I would become the first Frenchwoman to join him on the top of the podium. Very quickly, as there were very few competitions for us in France, we left to face the others in neighbouring countries. We 'made cars.’ Several of us would embark and left for Belgium, Spain or Italy. It was in those years, while passing the judo teaching diploma, that I met Paulette Fouillet, with whom I remained an accomplice, until her death in 2015 and with whom we formed the backbone of the future French women's team."

From the mid-1970s things did start to move. A first women’s French Cup was organised in 1975, the year of Jean-Luc Rougé's world coronation and then in the following year the first French championship took place in Agen, “With this first national championship, things gradually settled. I was a little ahead of the other competitors and quickly entered the French team. The eight years that I spent with that team were wonderful. I have immense memories. There was no real coaching. We were on our own. It was an adventure and it was incredibly exciting."

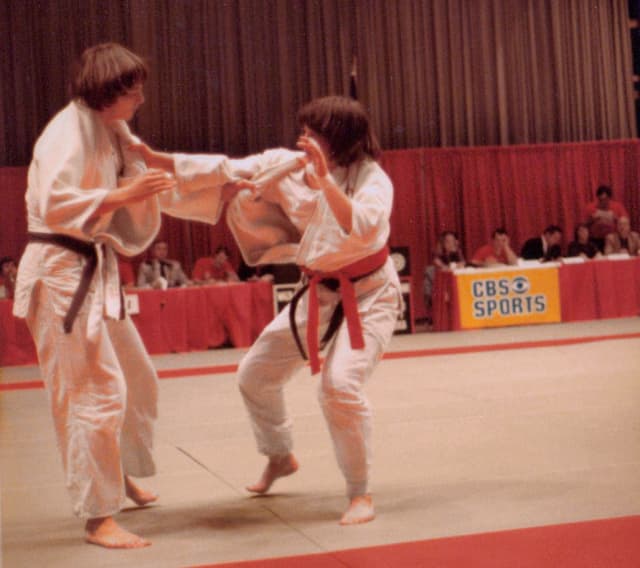

It is important to put things in context, because if these years were formative and they marked forever the life of Jocelyne Triadou, they were in the image of the fight for equal rights between men and women, “Somewhere we were fighting against the system. Not just that of the French federation at the time, but against society as a whole. For the coaches who were sent to the women's team, it was almost considered a punishment. The girls today do not really realise, but our best weapons then were our results. With the medals that we brought back from the European championships and in 1980 from the world championships, the federation had no other choice but to accept us. When we got our first major international results, some people said it was luck, but the French women's team has been lucky for over 40 years now so...”

You almost have to see in this climate of mistrust vis-à-vis women's judo, one more excuse to fight even harder and better, "We were lucky to have a strong ally within the federation: Josiane Litaudon, who later became General Secretary. She always supported us and she knew how to use her political position much better than we would have been able to do, because we were fighters. Together we tried to advance the cause of women. With our results and Josiane's work, we could move forward. On the tatami, we didn't really realise it yet, but I think these years have been crucial for the future of judo in France and in the world."

At the end of the 70s, just before the first world championships, the structures were still limited, “Yes, we had a French team and we were particularly united within that team, but there was not yet a training structure like today. We trained in our respective clubs. There was no permanent organisation and it was all very fleeting. It was only after New York that we gradually began to catch up."

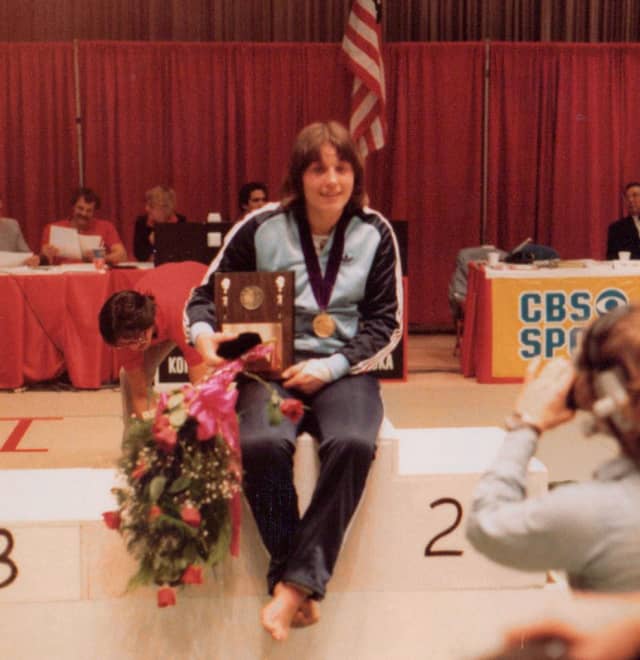

It is never easy to speak again of the detail of an event which took place forty years ago, time shaving the memories, yet Jocelyne remembers, “I remember the immense joy, but the astonishment also, to have won. The final was decided by the referees. It was complicated. It took me a long time to realise. I had been very late in my preparation because I had to undergo knee surgery. When I arrived in New York, I was still recovering and I had strapped my two knees so that my competitors could not know which one was hurting. There was no way I could miss this first championship. We were spinning in a loop in Europe, between the French and European championships only. I was so motivated, but if we take a closer look today, we realise that in the end everything went very quickly, between the stammering beginnings of women's judo and this first world event in the USA, only a few years had passed. This is due to Rusty Kanokogi. I am happy for having been a part of this adventure in my own way."

Before the competition itself, there was the arrival in New York, “It was amazing to arrive in the ‘Big Apple.’ We were staying in a hotel right across from Madison Square Garden and the first thing we did was to go for a walk in the streets. I remember the permanent wind. I also remember that due to my injury, I had lost a few kilograms and that, therefore, it was not too difficult to make weight. We were allowed US$10 a day to eat, but I could eat more! The federation did not want to reimburse me for the additional 5 dollars I would use. A journalist had therefore written 'Triadou, for 5 dollars more', for one of his article titles. At that time I was in a hurry and I did not understand why we did not have more. At a previous European championship, we were given tracksuits from the juniors and after the competition we were asked to return them. We refused. When I arrived in New York, I wanted my revenge."

The results obtained by the French team nevertheless marked a turning point for France and for the world, “after the championships, we stayed for ten days, shh, to party. It was well deserved. We changed hotel and we squatted in the rooms a bit. We really enjoyed this time. During the day, I visited museums and in the evening it was party time. It was at the time of the assassination of John Lennon and it was a rather strange atmosphere in the city. When I returned to France, the championship was already far behind us. I was greeted at the airport magnificently and following my world title my role as a municipal agent was made official. I was teaching judo in schools at the time. I also received a gift from the federation, which allowed me to buy a proper suitcase. For me it was already incredible that, thanks to judo, I was able to win some money. What was especially important was that at the level of the sports ministry they did not make a difference between men and women; they counted the medals and after New York and especially Paris two years later, women's judo in France became a real phenomenon. The results of this are still measured today, even if some continued to slander.

Frankly, I never cared about what people said. It was not my problem. I wasn't listening. All of that, for me, was not judo. Whether we are men or women, we play the same sport and we express ourselves with the means at our disposal."

Jocelyne has not lost her fighting spirit, she simply added a capacity for hindsight and analysis which commands respect, "Women's judo today is interesting, but it is different from ours. Girls have become pros who benefit from the power of a big machine. I wish them a long and rich career, like ours though. Sometimes I wonder if I could relate myself in modern women's judo. I don't know. We were fighting for ourselves, obviously, but also we fought against a system. Our strength was our cohesion. We wanted the same rights as men. It's that simple. It never went fast enough, always felt like a slog. Today this is so much better; there is no more distinction. I am very happy to have taken part in this social battle, but I feel there is no longer the same spirit. Sport has become more individual. You know, we even made petitions to denounce certain things and that was part of our strength.

When I look back, I tell myself that we were the source of something great and that everything we did was not for nothing. Sometimes I tell myself that I should write it all down, but I am not a writer. My friend Paulette has already left. Time flies."

To illustrate this incredible spirit that reigned at the time, Jocelyne slips a last anecdote to me, “When I stepped on the podium, I remember Mr. Matsumae, the then president of the IJF, giving me my medal. We were waiting for the anthem, but no Marseillaise. There was panic on board! We came down from the podium and a few minutes later, we got back on it. In the meantime, the French anthem had been found, so I had two ceremonies for the price of one. I remember the pain it must have been for Barbara Klassen, my runner-up because twice she had to go up on the second step. It was a moment of both immense joy and sorrow. We had fought, but we were one family. I often think of her, especially as she passed away a few years later."

If the years have passed, Jocelyne Triadou still has the assertive character that allowed her to become world champion. She says what she thinks and she embodies it. It is thanks to women of her caliber that today judo can be proud to be a sport in which fairness is a fundamental value.