“When I think about my times being young, at 13 or 14, that’s when I decided to train hard to be able to set goals. It wasn’t just about the goals themselves but about being in a position to be able to set goals. I did a lot of sports and I could have chosen any. I had to be able to manage my time really well. I was in a sports school from age 10-14, which helped a lot but then I changed to mechanical engineering from 14-19. The sports school for judo was excellent and the coach was really good but I knew that sport could not be my whole life, with there being possible problems and injuries in the future; there would not have been a possibility to achieve anything outside sport.

I was fortunate to have parents who really supported that decision. They were very sporty but also believed in education to open lives. We all knew that going only to sport school would mean reducing my chances for a good career after judo and also my ability to earn a living. I chose mechanical engineering and went for it so that I could have that variety even though I knew it would mean long days of training before and after school. I was training alone before school with some light weights and then cycling to school. I trained 5:30-6:30am. After school I went straight into judo training.”

Sabrina is clear that her way is not for everyone but it was necessary for her from the beginning to explore her goals and really commit to life decisions that enabled a variety of achievements, not just a single track.

“I knew for myself that to be Austrian champion and to get in the junior team to reach European and world championships, I had to manage my time that way. There was not really an assessment of it or alternative choice, I just knew that I wanted to do it so I was committed to that schedule.

Back then there was no internet but I bought videos of the 1995 World Championships in Japan and the 1996 Atlanta Games. I had posters of my role models in my room, like Koga and Udo. To look up to Udo was important because he showed us that we could beat the Japanese, with wins against Nakamura in both ‘95 and ‘96. I also read the British and German judo magazines.

My coach from the beginning talked a lot about the Olympic Games. He sparked the possibility to qualify and he made it possible in my head to one day reach an Olympic gold medal. He didn’t try to guarantee it but just showed us there were possibilities.

To improve technique my coach knew that it was better to bring experts rather than try to manage with everything himself. He showed a way to be open about my judo education and this gave me such confidence to always search for the right way without worrying about having to follow just my one coach. He was so open and that fed into all my future decisions.

What I realised later was that so many other club coaches wanted their players to follow them only and they struggled to step back but my coach was not like that. His openness and ability to allow transitions gave me the confidence to make decisions and that was truly why I was able to get strong as a junior.

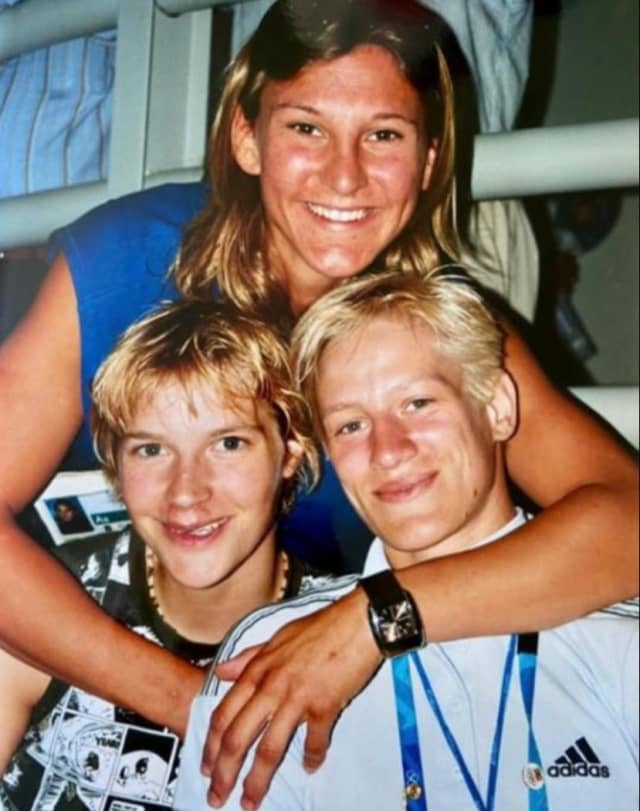

At 17 I qualified for my first junior world championships, in Columbia. I was so confident because I was winning all the tournaments that year, but I lost the bronze medal by hantei. It had been such a huge goal, set in my mind, that I couldn’t even speak about it for two days. I couldn’t set new goals. Once back at home I had a long conversation with my coach and he told me that I’ve had some of the best fights possible this year and missing the medal didn’t take that away, so I would win the gold at the Europeans 5 weeks later and I did. My teammate Claudia Heill won gold as well and Austria had never won two golds at that level. It was really important for the team.

From that time I knew I could win everywhere and had confidence that I was ready to start winning at senior level too. I had another year in the juniors and was on the podium again the following year. Following that first European gold, Austria took me into the senior team which made me really happy and proud. I was so proud, having struggled so hard, managing school and training and tournaments. I would study through the night sometimes and often only slept for 4 hours. I knew that with my aim to qualify the Games I just had to do it.

Around that time my club coach had been to China and he brought me back a picture of a Buddhist Stupa with three steps and he wrote on them, in order: European championships, world championships, Sydney Olympic Games. This was the first time the goals were made visible, even if they had been in my head for a long time. I hadn’t really voiced them and so this gift was very important for me, to solidify what I had to do.

I felt that at 17 I was still not exactly at the level I needed to be. I was losing some contests by very narrow margins and I was quite angry about those losses. Despite them I managed to qualify for the senior world championships and I knew that was my chance to qualify the Olympic Games. A 7th place at the worlds back then meant automatic qualification for the Olympic Games. I was the only woman for Austria to qualify that worlds in 1999.

At the Birmingham World Championships, at -52kg, I was in really good shape but I lost for the 7th place. Buckingham (CAN) threw me in the first few seconds and by one place I didn’t qualify the Games. At that time I was struggling a lot with my weight and so knew that to qualify through the European ranking system would be very difficult.

In April 2000, still at -52kg, there was the European Championships, the final qualification event. I was told I had to be in the top 5 to hold my European ranking to make the Games. I was fighting very well and had my first ever medal match at a senior milestone event. I fought the Russian for the bronze and in a tight uchi-mata and te-guruma situation we both landed on our heads and the referees discussed it for a long time. First I was given ippon but they scrubbed it off and gave me hansoku-make for the head dive. The team calculated again and the Russian overtook me in the rankings and I didn’t qualify the Games.

This taught me a big lesson about guarantees and gave me more confidence to decide on my own and to always approach each competition day in a way to not be finished fighting until the day is truly finished.

I went to Sydney as a training partner only and so I had a lot of time to reset myself and become even more professional. I studied a lot and I made the decision to change my weight category. I had to set new goals and I did that. I studied economics and Japanology through Bachelors and Masters degrees. I trained a lot, especially outdoors, things that were not possible during the Olympic qualification period. I enjoyed mountaineering, cycling and lots of different sports.

In the Autumn I fought in the world military games and won the title, the first of 6 and that helped me to begin to get confidence in the new weight class.

I set my goals really high, always. I was stubborn. I didn’t medal at a big event again until the 2003 senior Europeans at -57kg. In all that time, that 3 years, I was training as I needed to be to keep developing but what really kept me going was the focus on my studies. I was right at 14 to ensure I had more than just judo in my life.”

Sabrina has been world number 1, has two medals from the world championships and was European champion twice. She has competed at 4 Olympic Games despite missing out in both 2000 and 2004. “The struggle to qualify the Games twice and not make it was part of forming my total focus on always moving forward.”

"Now I look back knowing I couldn’t have guessed the future but I am happy with the decisions I have made. I don’t regret a single decision of my career. All the failures and injuries helped me to question myself. I analysed myself a lot and realised I enjoy competing, I enjoy challenge, whether in judo or other areas. It’s that process of being challenged and then solving it no matter how big the task seems, that was always important. With that in mind it wasn’t possible to fail. My reasons why were the foundation of the goals and I became so sure of those.

The inner attitude you have through failures can be more important than the winning. You can realise your limitations and therefore understand more about yourself. Once you don’t fear failure or making mistakes there is a freedom that enables commitment and improvement.”

I remember a member of my Austrian team, Ernst Hofer, when he became a youth coach, saying , ‘Talent is cheap. Dedication is very expensive.’ He was so right!