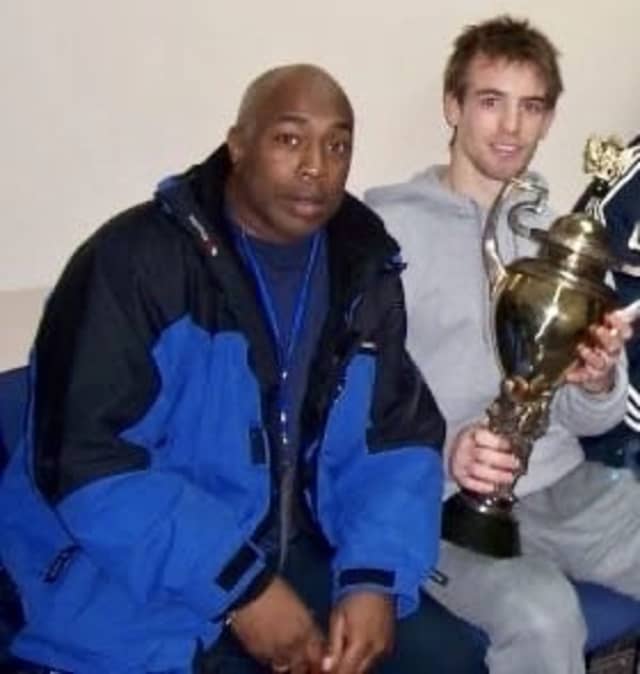

Fighting Films marked the anniversary of Craig’s goodbye with a live panel interview, hosted by production manager Jack Willingham. He welcomed Craig’s personal coach, Fitzroy Davies (GBR), alongside Darcel Yandzi (FRA) who was a big part of Craig’s judo development. The line-up was completed by Winston Gordon (GBR), a GB team-mate of Craig’s. All 3 men were very clear that over their years of working with, training with and travelling with Craig, their relationships with him changed and that was the key to their close bonds.

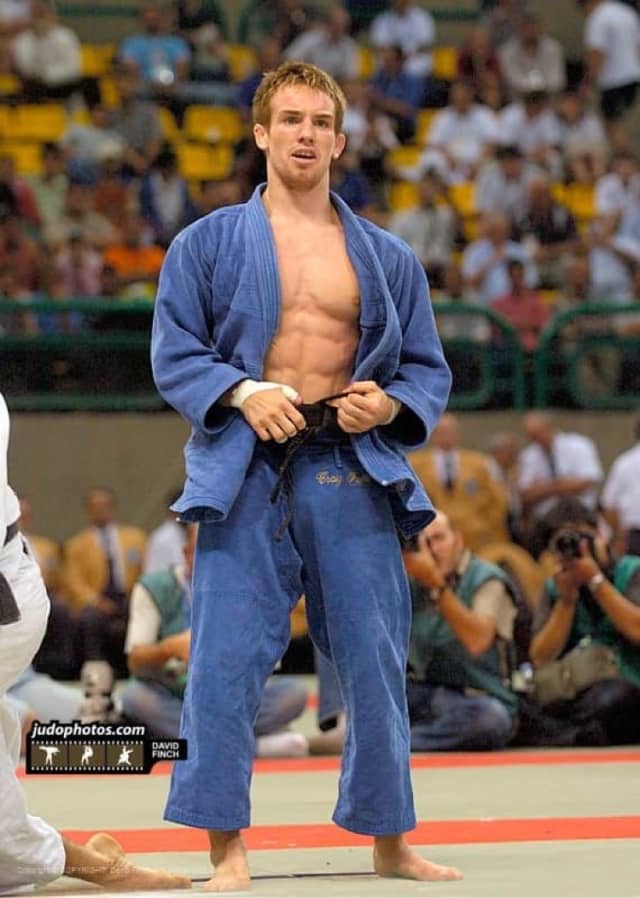

The interview delivered treats in the form of fun anecdotes and also outlined a brief history of Craig’s quite extraordinary career, from Olympic losses that he battled through, to topping the world podium in Cairo in 2005. A through-line emerged during the interview, though, that painted a picture of Craig that anyone who knew him could relate to; whether he was on a high from a win or struggling with a loss, he was always the essence of humility. Craig was humble, in the truest and most genuine way. As world champion he didn’t show-boat or shout about it. He accepted the result as with any result. The video of that win shows a gentle satisfaction as Craig re-aligns his judogi and goes back to his mark to bow. This was the real measure of the man.

Winston reflected on that time, “He knew he could do the damage. He’d beaten most of the people there. We (the rest of the team) imagined the result but he just went and did it! Even with such high confidence, he was still humble. He had a judo brain, a real master.”

That mastery was borne out of an accumulation of experiences, coaches’ input and plain old hard work. No elite athlete makes it by accident. Darcel, himself an Olympian and a world and European medalist, spoke warmly and candidly about some of the things that Fitz and Craig did so well. “Craig had a lot of people involved, but as his main coach Fitz had the real responsibility. Fitz was always open to bringing people in to work with Craig. Lots of coaches want to keep players, holding on to them, but Fitz and Craig had that relationship and trust so the things that were needed were found and that meant he could acquire all the pieces needed to ‘complete’ him as a judoka.”

Fitz added, “you know, a lot of people gave Craig coaching. I was more the person to talk to.” Here, other top coaches across the world will recognise the changing roles of coaches as they work alongside their judoka through a long career. Fitz was always happy to both guide and accept the changing relationship with Craig and with all his athletes. Allowing students to grow up and to make mistakes and to also flourish is imperative, but having the security of the personal coach right behind them is just so important.

It is understood that no-one can put an exact finger on the single reason Craig chose to end his life. It’s difficult for any of us to accept that someone so brilliant, so young, so accomplished and so well liked could leave in the way Craig did. It’s shone a torch on the state of play with regard to retiring athletes, mental health in sport and also on federation systems. Finding even small ways to improve provision in each of these areas can only be a positive and Fitz, Winston and Darcel agreed whole-heartedly with regard to these subjects.

Winston made his feelings clear, “After Craig stopped competing, with his results behind him, he went for two coaching jobs with British Judo and he didn’t get them. He was a big star with world and European gold! To not have that calibre of athlete involved makes no sense.”

Fitz added, “The financial investment from the Lottery and British Judo was huge and they just parked him. To not keep the benefits of that investment within is mad. Look at Karina and Craig and so many others. Just washed away. Not everyone can be a good coach but they can be taught, developed. I took Craig to schools and helped him to speak publicly. Once he felt more comfortable you couldn’t tear him away from coaching. Systems need to look after athletes when they retire. These guys should be taking over in years to come.”

Winston continued, “Look at the French coaching teams. They do their research and their apprenticeships. They give back. They want to give back! That hurt Craig the most.”

Darcel spoke here too, “They fight for their country. At the finish, contact is gone. It should be a continuous process, not a stop!”

Jack intervened, “What did we lose?”

Darcel spoke quietly, “I’m selfish. I lost my friend.”

The conversation turned to happier memories, with some funny stories and some inspirational judo moments. What next? This is the question that needs answering. To construct a way forward from this point and to make the behaviours and systems of combatting mental health issues in sport more meaningful and robust, is the focus. Judoka fight great adversity, usually on the mat, often off the mat. They will fight this too, but without exception, it is agreed universally that we are stronger in this together.

With World Judo Day approaching in October, this is the IJF theme for 2020, ‘Stronger Together’ and Craig’s friends and colleagues know just how important a message this is.

“Just talk, that’s all I can say,” said Fitz. Winston added, “Judo is a family unit. Silence is not the key. Know who your circle is and speak up. Like the coaching teams around athletes, you have to know the role each person plays and use that.”

Darcel, in his usual animated and passionate style contributed again, “This situation goes way beyond just judo. What can I do to make a difference in this crazy world we’re living in? I need to always put positive things back in, while I can.”

A year on, we remember Craig and we miss him.