We introduced the statistics, the almost impossible feat and the question in our first article in the series, which can be found here:

https://www.ijf.org/news/show/151-olympic-champions-tokyo-to-tokyo

A reminder of the question:

It could be said that to be in the company of an Olympic judo champion is to be presented with someone whom has reached an absolute pinnacle, a ceiling which cannot be surpassed; there is nowhere further to ascend in the world of sport. We often find Olympic champions speaking with freedom and certainty, unafraid to share an opinion, speaking of their lives and journeys with confidence. For many we feel there is peace, and that can be magnetic and inspiring.

So the question is, did they become Olympic champion because of that character or did they become that person having won the Olympic gold medal?

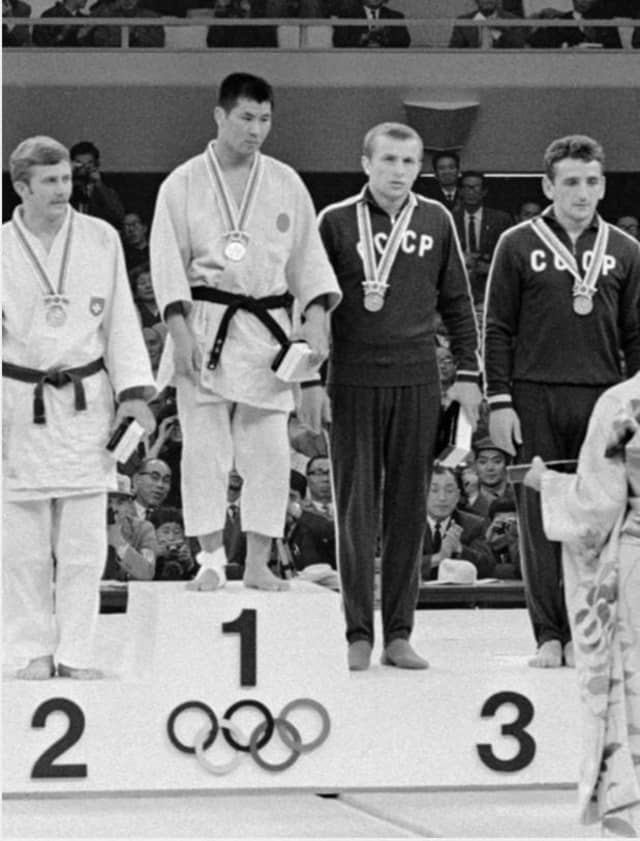

“In 1964, in Tokyo, it was the first time for judo to be accepted into the Olympic Games and there were just 4 weight categories. I was the lightest and it was me fighting first, so I received the first ever gold medal. There isn’t a character-related reason for this but I was very lucky and there were a lot of people who supported me.

Luck was the biggest reason for winning the medal but also, as one among the lightest athletes, I put my whole effort into my daily training to reach that first Olympic medal.

By default I created a way of working, a route to the gold medal and I was able to pass it on to the younger generations. I think I transmitted a good message to young athletes at that time because, from the 4 categories, Japan had 3 gold medals. Japan was the strongest country for judo and so I could contribute to the judo world and help our sport to become more popular. Many new, young ones began due to that event."

"For the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, all the other Japanese team members were chosen in advamce but my weight was chosen last and not until one week before the Tokyo Games. I was chosen and among our team of 4 athletes, I knew the others were famous and strong and had media attention. In the media there was certainty, they knew the others should get gold but the mass media didn’t speak about me or say that I would win. So in this situation I really wanted to win! From the four of us I wanted to be the first gold medal winner, to show the media that I did it, I won the medal and became a champion."

"I trained very hard and my private life was also just dedicated to the Olympic Games. When I was chosen I cried and was so happy. That moment increased my feeling that I should and could reach the gold medal. Of course I respected the other 3 very much but I really wanted to be first.

There wasn’t a big, immediate impact on my life. The media, of course, commented. I was in the media every day and they knew how big an achievement it was but other than that there wasn’t really an impact. After the Olympics, I didn’t feel so much; there weren’t the same feelings again as becoming Olympic champion, but when I was introduced to new people as the gold medallist from Tokyo, I felt a unique kind of happiness.

It is difficult to give an opinion about today but certainly the level in other countries has become very high compared to my time. I think the judo level comes from preparation of the mind, body and technique and all are high quality these days but to get to a gold medal is so tough in any era. I respect all the countries working hard to reach that top level.”

What do you remember about your Olympic Games competition experience?

“In 1964 there was a big difference between Japan and the rest of the world so Japanese people thought it was a regular thing to be judo champions, for the Japanese it was normal. This brought pressure. So, all my focus was to win, it was all I imagined. It should be by ippon and not any other way of winning. Being the first, I wanted to pass the good images on to the next athletes, the next Japanese athletes. When I became champion I was delighted to be able to create the right image. At the same time I felt my mission was completed and I was happy with that. I could answer the Japanese people’s expectation, that was the mission."

"In the final the win came from ashi-waza, for two waza-ari scores. I used ko-soto-gari and o-soto against the Swiss athlete. Everyone thought I would fight with Stafanovs in the final, the sambo athlete from Russia but following the draw, that ended up being my semi-final instead.

I really think judo is an educational sport and that is a very important aspect. Courtesy should be among all people and it’s especially important for judo athletes. After I stopped fighting, the judo education I had benefitted from fitted in with my work life. My work colleagues liked me as I showed respect to everyone and was a positive person.

Anton Geesink was a man I really looked up to and was impressed by. His tachi-waza and ne-waza were good but it was his attitude that was really impressive. I lived in Germany for three years after I retired from competition and the neighbouring country was the Netherlands so I was able to meet and train with him often.”

Now 82, Takehide Nakatani continues to enjoy his life in Hiroshima, maintaining his judo values and reflecting on a life of learning. He was the first, the start of it all and feels lucky to have had the opportunity to lead the way. He made the most of that chance and hopes all judo athletes in the future will make the most of their opportunities too.