History is the explanation of the past to understand the present and foresee the future. Jim Kojima´s history explains his modesty also highlighted by the restraint he shows when he speaks. Jim does not shy away from themes, he talks about what is asked of him, but he does it in a modest way, without adding drama. His story is the description of his own life without extra adjectives or superlatives. It is like the chronicle of a journalist. It is objective and neutral, although it could have fallen easily into the temptation of melodrama.

In 1942 Jim was a boy living in Richmond, Canada. Being Japanese or, of Japanese origin, in North America in the middle of World War II and after the attack on Pearl Harbour, was not the best calling card. It is essential information to understand a biography and the honesty of a man with enough experience to write an encyclopedia.

Tell us about your background.

I was born in Richmond and in 1942 22,000 Japanese people were evacuated from the West Coast of Canada to at least 500 kilometres Inland. Our family were taken to the next province, Alberta, to a sugar beet farm. We were allowed to come back to the West Coast, finally, in 1949 and our family moved back in 1951, to Richmond. Our parents started their lives from scratch two times. In 1942 everything was taken away from us and then when we moved back our parents started over again with nothing.

How long has judo been a part of your life and how did that lead you into working with the IJF later?

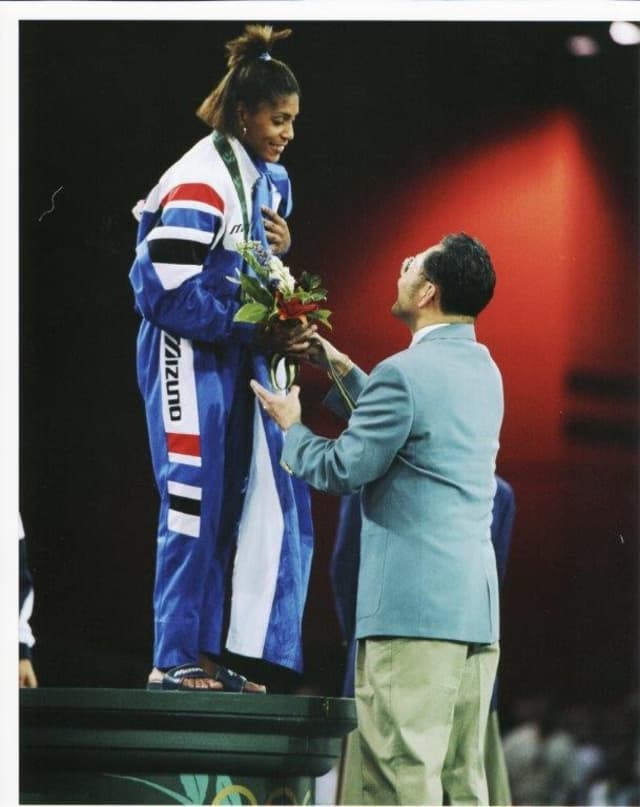

I started Judo in 1953 and became a black belt in 1957. I was President of Judo Canada from 1988 to 1994. I joined refereeing circles in 1958, becoming a Judo Canada National Referee in 1971, Pan American Referee in 1973 and IJF ‘A’ Referee in 1974. I was IJF Referee Director and IJF Referee Executive Member from 1995 to 2001. I refereed at two Olympic Games, 1976 and 1984 and I was a Referee Commission member for 2 Olympic Games, in 1988 and 1992. I was IJF Referee Director for two Olympic Games, 1996 and 2000. Through my involvement in judo I was honoured to receive the Order of Canada from the Canadian Government in 1983 and to receive the Order of the Rising Sun from the Japanese Government in 2011.

I still teach judo twice per week at the Steveston Judo Club and I’m a director at three non-profit groups in Richmond. I remain involved with Judo British Columbia and Judo Canada. After 67 years, I can say judo is my life!

Where were you in 1980 and what were you doing?

I was working for a company called Tree Island Industries, situated in Richmond, BC. I was teaching Judo at the Steveston Judo Club 4 days per week and refereeing at weekends and was the Vice President of Judo Canada. I was an IJF ‘A’ referee from 1974 and refereed in the 1st Junior World Championships in 1974 in Brazil, 1975 World Championships in Vienna, 1976 Olympic Games in Montreal, 1979 World Championships in Paris and 1984 Olympic Games in Los Angeles.

When the first Women’s World Championships was announced in 1980, did you think it was a good thing, another step or just a marketing strategy?

I was already in judo for 27 years and we had very few girls taking part. I felt that promoting judo for women was a good thing for our sport. Judo teaches many things, like learning how to fall properly, self defence, confidence and to persevere and keep going forward. Teaching the bow and respect and judo manners is very important and necessary. If we teach women good things about our sport and they are convinced that judo is good, when they become mothers they will send their children to judo. This was the first step to eventually get women included in the Olympic Games, which happened in 1992 in Barcelona.

Rusty Kanokogi worked hard to promote women’s judo in her club, in the USA and the world and wanted to hold a world championships to get more women into the Olympic Games. I heard she even mortgaged her house to hold the 1st World Championships in New York.

How were things during and after the event? Did you feel things moved forward or was it just an island In the middle of the sea?

The event was well run. To referee women only, movements were slower and the technique not as crisp as the men, due to this being such an early stage of inclusion in competitive judo. This tournament helped many countries to recognise that it was important to encourage girls to do judo. With women given the opportunity to grow in numbers and to practise and compete in many competitions, I felt that the level would become better. In some countries it helped to have men and women involved in judo for funding and support. It was also important to have men and women in the Olympic Games for the future. I believe that the IJF recognised that they must encourage and promote women’s judo more in the future.

Did you see a change in people’s behavior towards women practising sport and judo at the same level and with the same rules as men?

In the beginning men did not want to practice with women because they were not used to having women in a club. In smaller tournaments, in the early days, girls had to compete against the boys. This sometimes brought embarrassment when the boys lost the match. As the numbers grew, women had their own weight divisions and competed against each other. As the years went on in the clubs and training camps, it was no problem to practise between men and women. Coaches had to change their thinking and be open minded in coaching and teaching. I believe it opened people’s eyes more to the athleticism and skill that women have. The movement towards equality took a bigger step forward when women’s judo officially became an Olympic sport in 1992.

What are the main differences between 1980 and 2020?

The development of women’s judo has progressed technically and in numbers, becoming a demonstration Olympic sport in 1988 in Seoul and a full member in the 1992 Olympic Games in Barcelona. Women’s judo is accepted in virtually every country that judo is practised. It has become normal to have men and women involved in judo at every level, including refereeing, administration, teaching and promoting judo, but more representation in these roles needs to be encouraged.

Do you think there are still many things to be done on gender equality or are we right now at the same level on every field?

I believe that we are somewhat on the same level but women’s commitment to children and family is much greater than men’s. Women or mothers focus their changes to look after their children and family. We must understand this situation and find a way for women to continue longer in judo. Opportunities are now open to women in coaching and refereeing at very high levels.

Do you think judo is really building a better world in terms of a gender equity policy? In other words, do you think society is looking at judo as an example?

I believe that through the bow, value of respect and general judo manners on and off the mat, societies of the world look at judo as a model sport for their children. The philosophy of judo is to become a better person and to serve society. On a very simplistic level women are still underrepresented as competitors, coaches, referees, organisers and decision makers. We also do very little to support individuals, who identify as trans athletes and / or other gender diverse groups.

What do you say to those who believe that in the end the gender equity idea is just positive discrimination?

The term positive discrimination is an interesting one. Discrimination is the unjust or prejudicial treatment of different categories of people, especially on the grounds of race, age or gender and so the term ‘positive discrimination’ makes me feel uncomfortable, because nothing about discrimination of any kind is positive. If the intention is to suggest that one group is receiving more attention or resources directed towards them than another, then I would tell them that this is happening because when a gap or imbalance on one side exists within a system, imbalanced efforts are needed to achieve the parity or equity that we are striving for, so that everyone feels valued and respected as equals.