For decades women have been confined to a second tier, with competition being strictly prohibited and randori barely allowed. Although there was involvement from early on, in the development of judo, a long period elapsed before women were afforded permissions to step on to the tatami, in order to defend their right to obtain medals.

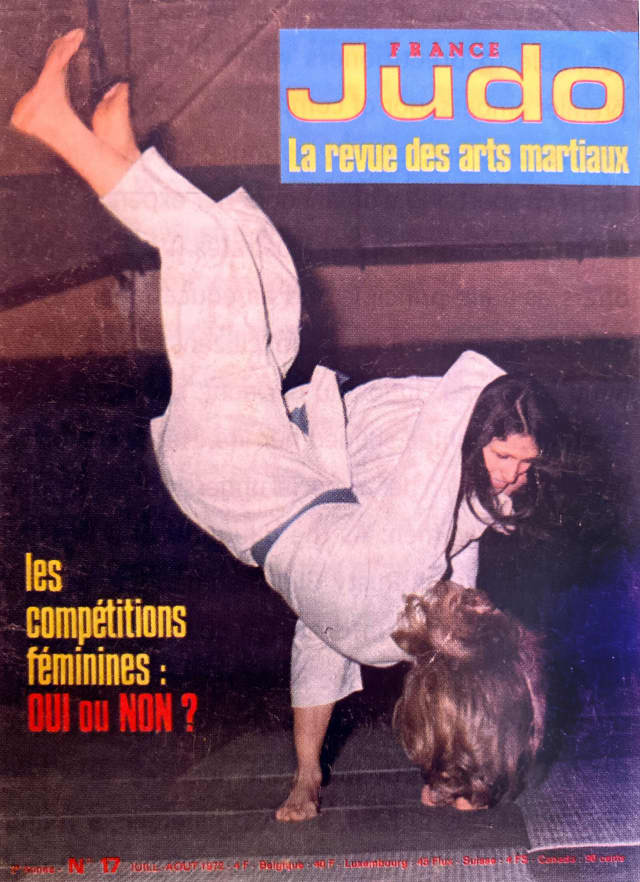

It was not until the advent of a woman with an exceptional career that women's judo stepped on to the tatami of the world with real, meaningful, public impact. A slight tremor had taken place in the early 1950s, when women had been temporarily allowed to compete in France and other certain countries such as Morocco, then a French protectorate, but all these first attempts remained isolated and were in vain. At that time, women who dared were the object of mockery and if they could participate in the grading examinations, they were denied access to the championships. Society was not ready yet.

The change did not really take place until the 1970s, when women's tournaments started to be organised in West Germany, Switzerland, Austria, then gradually in Italy and Great Britain.

To understand the obstacles that women had to overcome, we must dwell a little longer on the romantic story of Rusty Kanokogi. Through her career, she became the first great ambassador of women's competitive judo and throughout her life she never ceased to expand the possibilities of practitioners.

It was her experience as a young judoka, though, that allows us to better understand the assets and values that judo offers as a principle of life and as an educational tool to transform young people into "useful citizens for society,” as Kano Jigoro Shihan wanted from the inception of judo.

Rena 'Rusty' Kanokogi's early life (née Glickman; 30th July 1935 – November 21, 2009) was not easy. She was born in Brooklyn, New York and because of her family situation, she started to work at the age of seven, before becoming the head of a gang of girls in Brooklyn, called the Apaches. She really had to fight to survive.

She started to use her brother's weights and a punching bag at the gymnasium to train. By the mid-1950s she was married and became Rena Stewart, before having a first son, Chris, and quickly getting divorced. As a single mother, she was working as a switchboard operator.

"Fighting becomes my sport, for the spirit of survival and for the love of fighting," she said later. In 1954, at the age of 19, a friend showed her a judo technique that he knew. That was a revelation. She was immediately interested in judo, saying that she could feel how the sport would calm her down and help her develop self-control. Without hesitation, she learned judo in her local neighborhood and tried to compete but was barred because she was a woman. She acquired the nickname ‘Rusty’ after a local stray dog.

Nevertheless, she was authorised to train with men. Her physical capacities and her fighting spirit helped her to fight against the ambiant gender discrimination. "I was considered as an exceptional woman, a woman who practised like a man."

In 1959, Kanokogi finally competed at the YMCA Judo Championship in Utica, New York. Women were not officially barred from the competition, but she was the first one ever to try to participate. Actually there was no place on the tournament application to indicate gender, so she cut her hair and taped down her breasts. She was an alternate on her team, but when she finally stepped on the tatami, she won her contest and her team won the match. She was then pulled aside and the tournament organisers asked her if she was a woman. She nodded and was stripped of her medal. Rusty remembered, "My teammates told me not to go. Stay in the line and let them stew. But it was a choice between being humiliated in public and being humiliated in private. I chose privacy, so I stepped off the line." Rusty was re-awarded her medal during a special ceremony in 2009, some 50 years later.

Society showed its conservatism in a blatant way, so that such a situation could not happen again. The organisers added the word 'man' in the name of all subsequent championships. During the summer, Rusty participated in an international meeting on the Queen Elizabeth liner in New York Harbour. She fought a man and won. Overnight, she became famous.

In 1962, as she had no other possibility to train and improve her level in the USA, she traveled to the Kodokan in Tokyo, Japan. For many years, women had trained in the institution on their own and they couldn't mix with men. It didn't take long for Rusty to show that she was far stronger than all opponents training at that time and she was allowed, for the very first time, to train with the men. She was quickly promoted to the rank of 2nd dan by Kano Risei, the son of Kano Jigoro Shihan. Kano Risei was the President of the Kodokan at that time. Television cameras and journalists came to see the ‘American mother.’

While at the Kodokan, she met her future husband, Ryohei Kanokogi, who held black belt status in judo, karate and jodo and was on the Nichidai University judo team. The couple married in 1964 in New York and had a daughter, Jean.

Back in the United States, she continued to teach and train. In 1965, Kanokogi directed the first junior judo tournament held in New York: the New York City YMCA Junior Judo Championships. The following year, she directed the New York Women's Invitational Shiai. In 1971, the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) decided to allow women to fight among themselves but following specific regulations for women's competitions. Techniques were modified to limit the intensity of bodily contact, which eliminated a large part of the work on the ground.

Such a proposal was deemed inappropriate and unacceptable, by women who demanded equal rights. Rusty and others were fighting this decision and they won their case. A new regulation started to be used from 1973. The first national competition of the AAU took place in 1974.

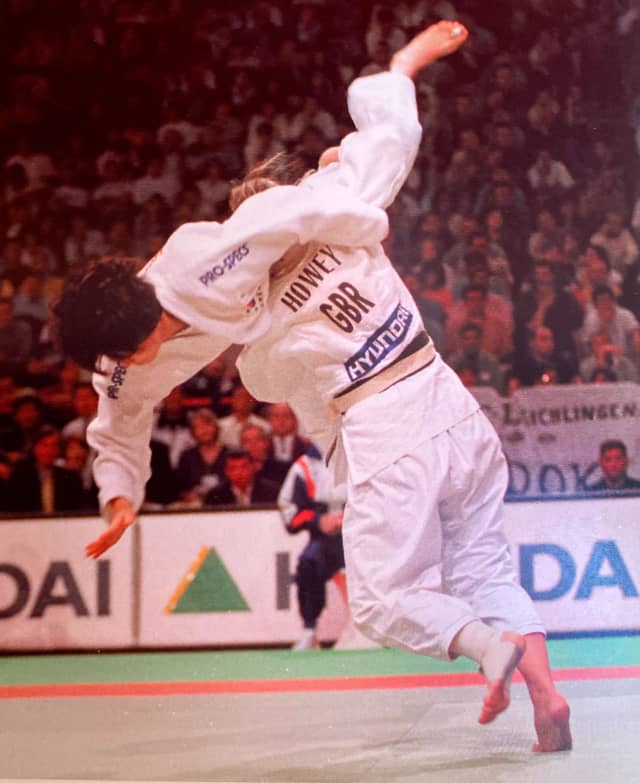

Following Rusty Kanokogi's example and due to the expansion of women's judo, the European Judo Union organised a first experimental competition in 1974, in Genoa, Italy. The following year, in Munich, Germany, the first Women's European Championships were held. A similar evolution happened around the world. The first Oceania Women's Championships were held in 1974 and in 1976 Pan-America followed and in 1978, Japan.

Time had come for women's judo to become global. In 1980, Kanokogi organised the first women's judo world championship in Madison Square Garden, sponsoring it through the mortgage of her own home. She was also the driving force behind the introduction of women's judo at the 1988 Summer Olympics and in Seoul she was coach of the first United States Olympic Women's Judo Team. She would coach her personal student, Margaret Castro, to a medal at these Olympic Games. Women's judo was fully integrated into the Olympic programme in 1992, in Barcelona, Spain.

In 1991, Rusty Kanokogi was inducted into the International Women's Sports Hall of Fame. She is also a member of the IJF Hall of Fame (https://www.ijf.org/history/hall-of-fame/1010).

Following in Kanokogi's footsteps, Clare Hargrave of New-Zealand was the first woman to obtain her international refereeing licence, in 1981. Today female referees are more and more present on the World Judo Tour. A first IJF seminar for women was held in Berlin in 1998, for the referees and one was held in 2006, in Fukuoka, for the coaches. An international conference took place on the occasion of the Rio World Championships in 2007 and in 2018 the IJF organised the first Gender Equity Conference, under the leadership of Dr. Lisa Allan.

Rusty Kanokogi passed away on 21st November 2009, in New York. A street in the city was named after her and she was hailed as an American woman who became known as the ‘mother of women's judo,’ for her efforts to bring equality to our sport, within the Olympic movement.

Source: Judo for the World by Michel Brousse and Nicolas Messner - IJF July 2015