The organizing committee specified that ¥500,000 were granted for the building of a 'Budo Hall' meant for the event. But the 1940 Tokyo Games never took place as they were cancelled because of World War II. This first Asian meet has been forgotten, so was the first inclusion of Judo in the Olympic programme.

It is known that Kano Jigoro and Baron Pierre de Coubertin were in regular contact. Kano's wish to give judo a universal dimension cannot be doubted. Throughout his life he tried hard to have his method spread abroad and the man travelled tirelessly to promote it. After he had set up the necessary structures on the American continent, he tried to develop Kodokan 'branches' in Europe and more particularly in Great Britain.

Richard Bowen gave an account of the conversations held in London during his visit. “Kano arrived in 1933 accompanied by his son-in-law, Takasaki Masami and Kotani Sumiyuki, both 6th dan. This visit nearly changed the course of British judo. On 26 August 1933, during a meeting of the Budokwai committee, Dr. Kano announced that he wished to merge the Society with the Kodokan, creating a London branch of the Kodokan. A general meeting of the society was called and it was agreed that the Budokwai should become a Provisional Branch of the Kodokan. The only point of disagreement was that while the members wished to retain the name Budokwai in some form, Kano was not keen on this, he wanted any new entity to be known as the Kodokan, London Branch. [...] The proposal for a Kodokan branch to take over the Budokwai ultimately collapsed, almost certainly because of the worsening international situation. But even shortly before his death in 1938, Kano was still talking about a London Branch of the Kodokan.“

It is difficult to be sure that Kano wanted to have judo immediately included in the Olympic programme though, as he was so attached to the educational dimension of his invention. The comment he made in a letter he wrote in 1936 to Koizumi Gunji gives an idea of his mindset at that time: “I have been asked by people of various sections as to the wisdom and the possibility of judo being introduced with other games and sports at the Olympic Games. Of it be the desire of other member countries, I have no objection. For one thing, judo in reality is not a mere sport or game. I regard it as a principle of life, art, and science. Only one of the forms of judo training, so-called randori or free practice can be classed as a form of sport. Judo should be as free as art and science from any external influences. And all things connected with it should be directed to tis ultimate object, the ‘benefit of humanity’.”

The British historian Syd Hoare and the French Yves Cadot agreed in their analysis of the article "Judo and Competitive Sport", written by Kano in November 1929. Official competitions were only one aspect of the practice. Victory in championships could not be an aim in itself. Kano was not against public contests: “When it comes to the question whether to show this competition to the public and to make it widely understandable to the people or to keep it privately in a dojo as in former times I think that showing it competitively is a good strategy for breaking these old private customs.“

His major preoccupation was his desire to keep judo away from professionalism among practitioners. Kano, who adhered to the views of Coubertin, defended amateurism. "I approve of the competitive exercise that we do now if it is done as exercices by gentlemen amateurs.“

Nevertheless, the 'olympialization' process of Kodokan judo was rooted on the one hand, in the evolution of the sport phenomenon in Western societies, and on the other hand, in the complicated political situation in the years 1930-1940.

The interwar years were a period of turmoil. As judo progressively became international, another move must be added, a "sportification' process, which was very powerful in Japan and in Europe. Kodokan was not the only organizer of championships. From 1914 onwards, the competitions between schools and university colleges, Kosai Taikai, under the supervision of Tokyo University became more and more frequent. Syd Hoare mentioned other events: “There were also a number of major competitions during this period which were performed before the Emperor. Typical of these was the Tenran shiai of the 1929 Enthronement Commemoration Budo championships. The judo event was held within the Imperial Palace grounds in Tokyo and was strictly organized by the Imperial Palace police.“

The Kodokan organized the first Japanese Championships with the assistance of the newspaper Asahi Shimbun, in 1930. The contestants were put in two different categories, 'specialists' and 'non specialists'. Later, age categories were introduced. In Europe, a similar orientation took place. The oldest international competition ever recorder seemed to have been the one in which the Japanese fought the Russians in Vladivostok in 1917. A national Championship took place in Italy, in Rome in 1924. But sport judo grew mostly in Germany. International meets occurred regularly. In November 1930, two teams from Frankfurt and Wiesbaden went to Great Britain and successively fought in Ealing, Cambridge, Slough, in the London Budokwai and in Birmingham's Midland Judo Club.

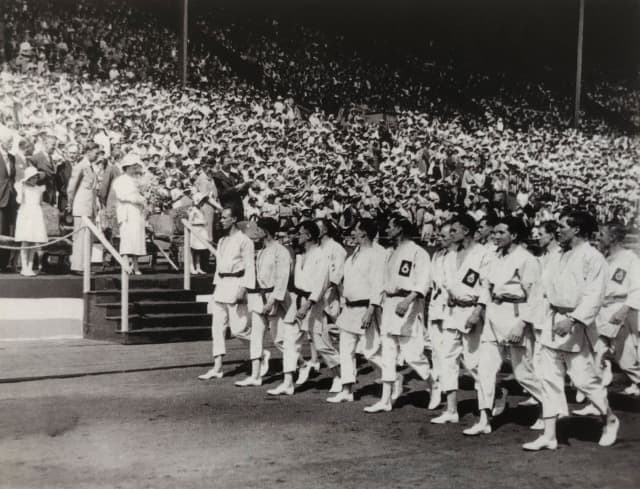

In 1931, the second Workers Olympiad took place in Vienna, Austria. The Japanese method was billed. The Austrians won in five of seven weight categories. A triangular tournament took place in November 1935, again in Frankfurt, with the German, the British and the Swiss teams. The records of the 10th German Judo Championships, 16 to 18 October 1936, named 91 contestants representing 32 clubs. Three age categories and five weight divisions were disputed: -112 pounds, -125 pounds, -140 pounds, -160 pounds and over 160 pounds. In 1939, 220 judo associations were listed in Germany. They numbered 7957 members, among whom 68 women.

Before World War II judo developed a lot in Germany and in Europe. The sport started to be added to the army and police training programmes. Already in August 1932, the origin of the creation of the European Judo Union (EJU) can be found. On 11th August, Koizumi Gunji and Marcus Kaye representing Great Britain, Mr. Bärtschi representing Switzerland and Alfred Rhode representing Germany drafted the statutes of a new organization. The objectives planned for the new association displayed deliberate intention of the signatories to align judo with the principles of sport, as they existed at the time. The policy centered on five items: to maintain close links with the Kodokan, to organize a European championship, to take into account the various categories between judo players for the promotion of judo, to define training and fighting rules and to introduce judo in the Olympic Games.

In the 1930s, the organisation of sports varied widely according to countries. In fact, the European Judo Union brought together the most representative clubs of their nation. This was to be modified in the immediate post-war world, with the growing involvement of governments on the management of sport practices. The creation of a national federation becoming the norm, the representativeness of the countries became official. However it is neither possible to ignore the creation of this first European Judo Union, nor its statutes which were to be used as foundations in the 1948 reconstitution. Progressively the number of the countries that formed an alliance grew. Austria, Romania, Czechoslovakia and Hungary joined Germany, Great Britain and Switzerland as well. Contacts were made with the Jiu-Jitsu Club de France in Paris, however the international situation was such that Moshe Feldenkrais failed to answer the invitation.

Among the Japanese communities in the United States, the number of judo competitors grew during the 1930s as well. But their logic was different. Even though competitions were seen as important they did not deviate from Kano's philosophy. As a rule, they were team competitions less likely to value the individual as such. The only criteria used to sort out participants into different categories were age, expertise, and dan eventually. The objectives were exchanges between clubs and challenging meets. The multiplication of these types of event was linked to the development policy of black belt associations, Yudanshakai, which were progressively set up. All those organizations were under the control of the Kodokan.

Two main directions could be distinguished. On one side, in geographical regions where Japanese presence prevailed, the directives of the founder were applied stricto sensu. On the other, in centre Europe, because of the influence of the boxing and wrestling traditions, judo was assimilated with combat sports which were already structured and had their own set of rules. The world conflict, which flared up on 1 September 1939, had final consequences on the sport orientation of international judo.

In Japan, the practice of martial arts in schools was made compulsory as early as 1931 in order to promote bushido and the Japanese spirit, yamato damashii. Martial arts replaced Western sports. After Japan's surrender on 2 September 1945, General MAcArthur who served as Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers began the demilitarization of Japan, according to the terms of the Potsdam Agreement. On 22 October 1945, following his orders, the Japanese Ministry of Education was ordered to forbid all types of military teaching. Martial arts were eliminated from the physical education curriculum of schools and universities. But private institutions that kept away from rifting off into ultranationalism were allowed to stay open. This was the case for the Kodokan. And immediately after the war the Kodokan opened its doors to the Allied Forces, and many trained there.

A confidential report issued by the Ministry of Education on 20 February 1947, read: “Since the termination of the war, lovers of judo, kendo and kyudo have voluntarily built them up as new sports.“ After a five-year ban, on 13 September 1950, the reinstatement of school judo was made effective, following the Japanese request for the return of school judo, in April of the same year. The reinstatement was subordinated to one condition. Judo had to choose a sporting orientation and keep away from Bushido. A new era began. In November 1948, Judo, the Japanese official magazine announced to its readers: “Judo is born again, and as a sport it is back on the path of prosperity.“

Source: Judo for the World by Michel Brousse with the collaboration of Nicolas Messner

READ THE FIRST ARTICLES