We introduced the statistics, the almost impossible feat and the question in our first article in the series, which can be found here:

https://www.ijf.org/news/show/151-olympic-champions-tokyo-to-tokyo

A reminder of the question:

It could be said that to be in the company of an Olympic judo champion is to be presented with someone whom has reached an absolute pinnacle, a ceiling which cannot be surpassed; there is nowhere further to ascend in the world of sport. We often find Olympic champions speaking with freedom and certainty, unafraid to share an opinion, speaking of their lives and journeys with confidence. For many we feel there is peace, and that can be magnetic and inspiring.

So the question is, did they become Olympic champion because of that character or did they become that person having won the Olympic gold medal?

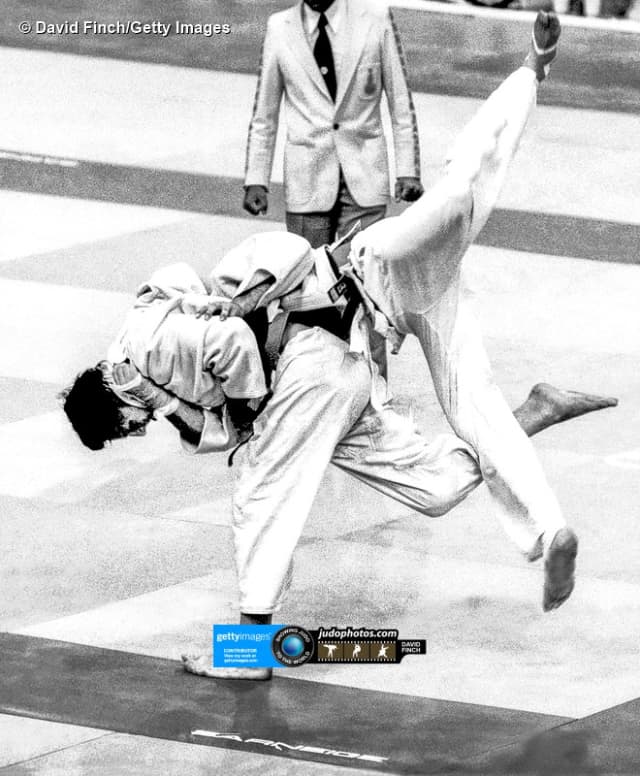

“It’s a combination of the two. First, we must understand that you can DO judo and you can BE judo. An Olympic champion is someone who IS judo. It takes time to get there and the way to get there is to find unity between body, mind and techniques. I would say you need 15 to 16 years minimum.

The path must give sense to your life. Without this sense you can do judo but not become the champion. Through the path we understand it is a bumpy road of wins and losses. In your mind you want to be the best. From the very beginning of my life I was in competition, it is everywhere in life. I was 3.5kg when I was born and another mother had a 4kg baby, she competed, there was at least a comparison, the idea of competition. 80% of the world’s capital is with less than 30% of humans and this is also competition, in economic terms. You cannot become 100% every day but you also cannot be satisfied with just a little bit. You must compete if, in your heart, you are passionate."

"You also have to like the training. We can look at the Games and see that it’s easy to win 5 fights but what is interesting is what you don’t see. It’s the commitment and sacrifice to make the right choices, saying no to a lot of other things.”

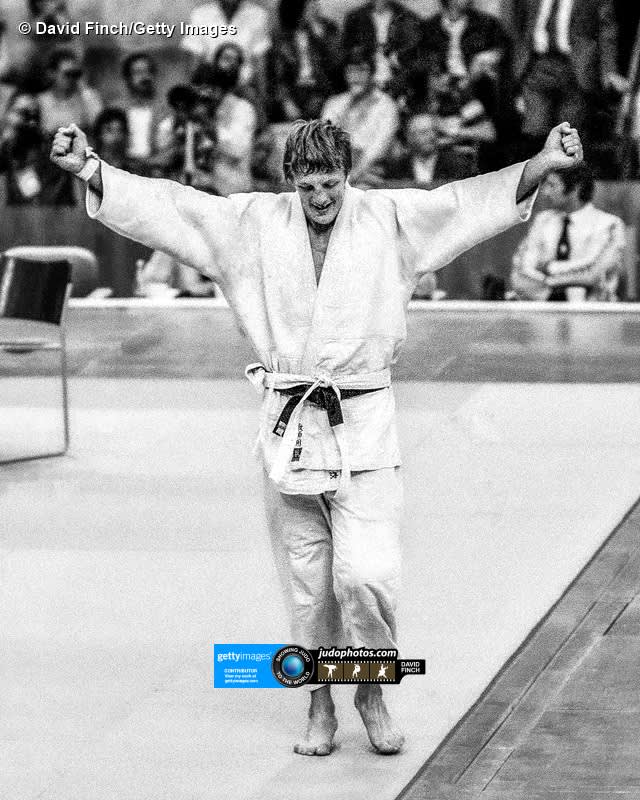

Everyone who arrives at the Olympic Games wants to win it; why Robert Van de Walle?

“The more people didn’t believe in me, the more I went for it. Giving up is not in my dictionary, even with injuries. I took part in 5 Olympic Games and people said at the last one that I was too old but I continued. I became Olympic champion in 1980 and I didn’t change as a person because of it but others around me changed a lot and then their approach to you means you change too in some respects."

"To become the champion is hard but to do it again is much more difficult. Four years later, in 1984, I lost my first fight. Coping with defeat is also hard but a true champion can manage losses well. The chances to win are always lower than those to lose and even if the statistics are on your side and you know the opponent well, 80% of success is mental and everyone really wants it. When you are truly committed to it, though, you have no barriers, you can unblock the things that try to limit you. Adaptability, creativity, flexibility, maximum efficiency and use of body and mind; everything in life can be illustrated on the judo mat.

I am in the same spirit now and I still dream about doing judo. Sometimes my wife wakes me and says I was fighting again in my sleep. It’s not just about winning but to be on the mat and feel the tensions, smell the particular sweat of the training rooms and enjoy the travel."

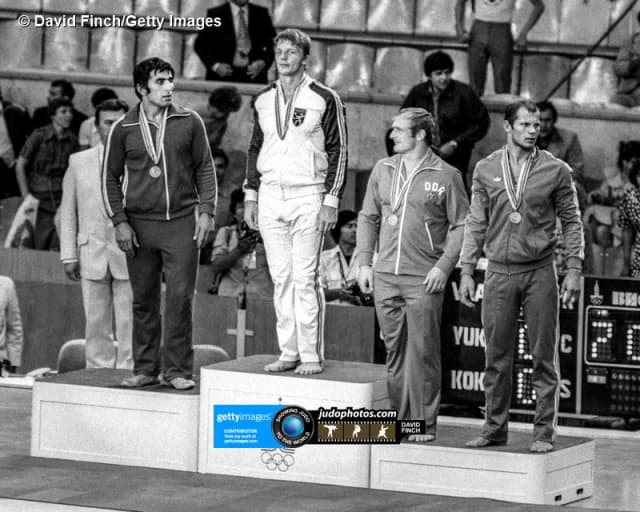

"My biggest opponents from my competition days are today my biggest friends. My Russian opponent and Jean-Luc Rougé are strong friends. It’s a kind of situation where winning and losing are no longer important; we are really a small family and it is about what we shared and what we understand of each other. The competitive life is over very fast and it becomes about what we do with this interesting experience. We have learned how to be resilient physically and mentally.

This is a path you don’t do alone, you need people around you who are motivated; there is a physio and technical support. In my day there wasn’t money to pay a trainer, it was all contributed for free. When I stopped I had debts with the bank too but it was worth it.

People influence us and after the gold medal we have to manage that. From one moment to the next you gain a lot of ‘friends’ and indirectly this influences you. The art is to stay with two feet on the floor and stay humble as we are only ever specialists in our own area of expertise. In other worlds we are not experts, in business, or as a journalist, or a hockey player. This humility is a very good quality, a necessary one to have. It allows us to keep learning. Once you’re a winner, not so many people will come to give feedback but if you are humble you can continue to learn and ask for support. You can always learn from everyone. If I wasn’t physically limited now, I would still stand on the mat to learn the new techniques of today.

I won the Olympic final having lost against the same man in the final of the worlds but the moment you think you cannot win, you put yourself under unnecessary pressure. I spent one year practising against one special technique and also applying my own counter and in the final of the Games it worked and I beat him for the first time; it was a double victory."

"When I was beaten in Los Angeles by an American in the first fight, I tried to understand why I lost. I could blame a referee or the rules but from that moment I started to think more deeply about my place. I thought about what I could have done better myself. I was Olympic champion and everyone expected me to win a second time. I was then afraid to lose and so I lost my stability. I did everything to not lose and nothing to win, the opposite of how I had approached the previous Games which had been all about winning and overcoming huge obstacles.

In Seoul in 1988 I met Ha (KOR) who was Olympic champion in Los Angeles but in Seoul he had become afraid to lose too and I understood how he felt. In Seoul I waited for that and I beat him and ended the day with bronze; my fear had gone. From one Games to the next I understood that I could lose my competencies and once I understood this I could fight against it.

It’s also a little bit about what you get from home. Not working didn’t exist in our family! It was ingrained, to always work step by step. My father educated me to never give up and to work to put the advantages on my side. I wasn’t a good academic student and as he was an electrician it was logical to follow him but I didn’t want to. I was 13 or 14 when I started judo and I had some physical ability. It was much more a minority sport then and no-one knew what judo was. I was intrigued by the Japanese names. We still had straw mats and the strange clothes; it was mysterious. After training there was speaking from the masters and the talking, the ‘mondo’ made us dream. Maybe we have to dream it in order to make it real. I think I felt some magic when I first began and I kept it with me.

It was important to come into a group of people who also wanted to promote good judo and could join me on my path. I began to get results and it felt good. I was so passionate about judo and still am today.

Are you doing judo or ARE YOU judo? I was happy to lose by ippon and not win by shido. To make ippon requires timing, technical choice, correct distances and so on but with a shido, no, this is excluding these important factors and when athletes try to get the other a shido, none of these principles are obeyed.

I ask myself these questions while looking back: did I live, was I loved and could I make a difference? I lived a fantastic life and I still do. I made life difficult for myself to be the best of the best but I lived and it is a fantastic experience. There is a little regret that it is finished and I won’t feel it in the same way again. I have been loved and still am. I still try to make a difference, maybe indirectly for a lot of young people. I did seminars for more than 20 years and I think they made a difference. To make a contribution to society is the purpose. I did it my way and inspired some, maybe. Without the medal I couldn’t have had my working life and I couldn’t have grown to have the confidence to do what I have done since. I wouldn’t speak the three languages I do now. I have been a head of delegation for Belgium at the Athens Games. If everyone spent time trying to be an athlete, maybe the world would be better.”