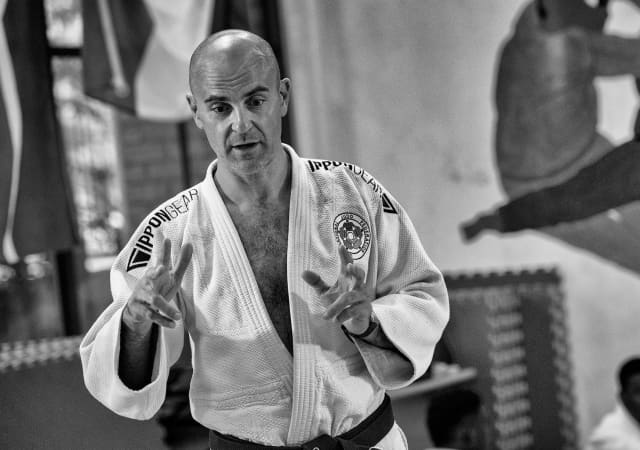

Born in Milan at the end of the 1970s, in a family from Monopoli, in the south of Italy, Roberto was not destined to find himself the backbone of the development of judo in Hillbrow: “I started judo when I was a teenager. I had practiced team sports a bit, but that didn't really suit me. I needed to do a sport where the result depended only on me. I tried some martial arts, but I didn't like to kick. I pushed open the door to the local judo club, unsure of what to expect and fell in love immediately with the sport. It was love at first sight."

Smiling, Roberto explains that he was an Italian teenager with a Vespa, like many, a little rough at school, not necessarily turned towards others: “As soon as I started practicing judo diligently, I imposed on myself a better lifestyle and I started to internalise the philosophy of Jigoro Kano. I did a little competition. I was taking my Vespa to travel as far as I could to train. I liked the smell of the dojo. But when I passed my blue belt, I had a road accident that kept me away from the tatami. After having more or less recovered, I returned to the university where I continued to do judo, but unfortunately not as intensively as I would have liked.”

At the end of his studies around international relations and development, he decided to go beyond his Italian horizon and began to work on behalf of NGOs which took him to the DRC, to Somalia, but also to Ethiopia where he took care of water, Guinea Conakry where he worked on the Ebola epidemic, Central African Republic, Turkey, Lebanon and finally South Africa: “When I was in Ethiopia for four years, I felt that I was no longer really fit. Something was missing. But above all, sometimes I did not feel safe. With an Armenian colleague, a former judoka like me, we decided to go back to judo. We were brown belts, but as in a world of blind people, one-eyed people are kings, even if we didn't have a black belt, we were the kings (laughs). I met Johannes Daxbacher (IJF Military and Police commission and Judo for Ethiopia programme) who was on a mission there. He made me earn the precious black belt. It really made me want to know more technically and pedagogically. I will always be indebted to him.”

With this desire to learn, Roberto discovered that the International Judo Federation launched their Academy: “I signed up for level 1. Very quickly I met incredible people like Daniel Lascau, Mark Huizinga, sensei Mukai of the Kodokan and Envic Galea, the Director of the Academy. They pushed, encouraged and motivated me. I wanted more. Once Level 1 was in my pocket, I continued with Level 2. Envic inspired me enormously and he asked me if I was interested in working with refugees. I said that obviously I was interested.“

After a last mission in Turkey, Roberto was again asked to take charge of a brand new programme launched by the IJF in South Africa. He then left his job and went on a first recognisance mission to Johannesburg: “I was at this time in my life in Turkey, but I had the feeling that I belonged to Africa. I could not refuse such an opportunity. There are trains you have to get on. And you know, for me who hates flying, getting on a train was obvious (laughs). I knew about working with refugees, even if it was more from a logistical point of view, but I didn't really know the sports side of the aid effort.I had everything to learn and I really wanted to. During this first mission, I analysed needs and started to set up the structure which today allows me to take care of almost 650 young people in 7 clubs and 3 schools in Johannesburg, while we also started activities in Pietermaritzburg, Bloemfontein, Port-Elisabeth and Cape Town.“

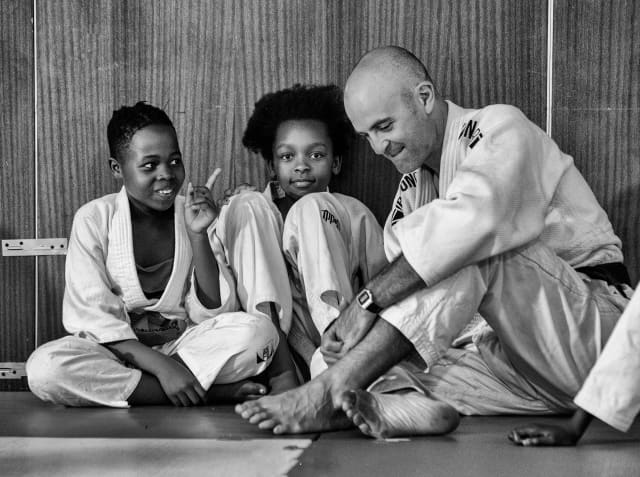

With the support of the UNHCR and the Jesuite Refugee Services (ONG), three places were quickly identified: “There is so much to do and for the moment, we only cover a very small sector. The IJF's help has been wonderful. Tatami and judogi have been sent in large numbers and I can always count on their support. If I take only the case of Hillbrow, where I am based, there is an incredible demand for social cohesion and child protection. The needs are enormous. Xenophobic attacks are legion, the population is very mixed, crime is common. I try to develop a maximum number of partnerships with the UNHCR, the local NGOs, the authorities. I work hand in hand with the National Federation. It is of great help. I am convinced that with judo we can change some things. In the dark, judo is a spark that can light a big fire around which the children of Hillbrow can come and have fun and smile.”

To the question of risk that living and working here includes, Roberto is clear: “Fear is a perception. Sometimes you don't really realise the danger you live with, but what is certain is that when you choose such a profession, risk is a factor to take into account. Frankly, if you want to change things, you have to take risks. Life only makes sense if you put yourself in danger.”

While his girlfriend is waiting for a happy event in April, 'Coach Roberto', as his pupils call him, continues to dream and work on a daily basis: “My dream is to see the IJF programme take on even greater dimensions. I want to transmit to my young people the desire to move forward, the desire to believe and hope. I would like them to be the leaders of tomorrow and the leaders of their own lives. I want to keep fighting to find funds. Everything cannot be based solely on the support of the IJF, whose generosity is already monumental. My ultimate dream would be to see one of these young people one day become a great judoka and also to see my future daughter doing judo.”

If there is a lot of darkness in Hillbrow, there is no doubt that the dynamism instilled by Roberto is perhaps the spark that one day will make people speak of this district in other words than those attached to violence and crime. Beyond the resignation of living here, there is now hope for a better world and that hope is called Judo.