Leandra said, immediately after she returned from the border region, “The night before we travelled to Syria, I almost couldn't sleep. I was excited, nervous, scared, trembling. It even went through my head that I might not go back home to see the ones I love. I didn't know if I would hug them again! This is what I really felt during that night.”

We are bombarded with images in the mainstream media, that cloud any judgement we might wish to make in objectivity. We have pre-positioned expectations, but what is always missing is the 360 degree view of the individuals, each with their unique understanding of what it is to be human.

“After we came back, I could say that I saw, with my own eyes, the war, the suffering, the wounds, the scars, the empty looks as if there were no souls left in those bodies."

For Nicolas it came with a vivid daydream, "Before crossing the border, I had the feeling of jumping out of a plane without a parachute, maybe with a guy pushing me out of the cabin and shouting at me 'Don't bother my friend, there will be someone on the way to pass you one!’

Through the whole day, 5th April, we sank into what people call 'enemy territory.’ It's a misunderstanding because it is not the territory that is the enemy but what some people do within it. The vast majority of the residents of the region did not ask for anything and especially not that. They just longed to live, when now they are trying to survive. The difference is massive."

Nicolas has traveled to many challenging regions, all over the world and is adept at understanding each new environment and each new set of customs and potential threats. Syria is different.

“In recent years, I have been to Kilis several times, on average once a year since 2016. So I have had the opportunity to approach the border. However, what there was on the other side I could only imagine, almost fantasise about it and I came to wonder if there was really something beyond the barbed wire. I had seen, on a clear night, the light of the bombardments above the horizon. I had heard the bomber planes more than I had observed them. I had heard the explosions of rockets fired at Kilis, but suddenly everything was becoming real and metre after metre I was overlaying words and images on top of my mind’s guesses. The first kilometres are a sort of dismal sandwich between rows of fences and barbed wire, dotted with checkpoints, on which a swarm of soldiers, armed to the teeth, lurk. On either side of this corridor, there is nothingness. It’s a no-man’s-land where life is denied. On this road between two worlds some authorised vehicles circulate, like ours. Silhouettes stroll, whose destinations remain a mystery. When the last barrier approaches, then Syria hits you by the throat."

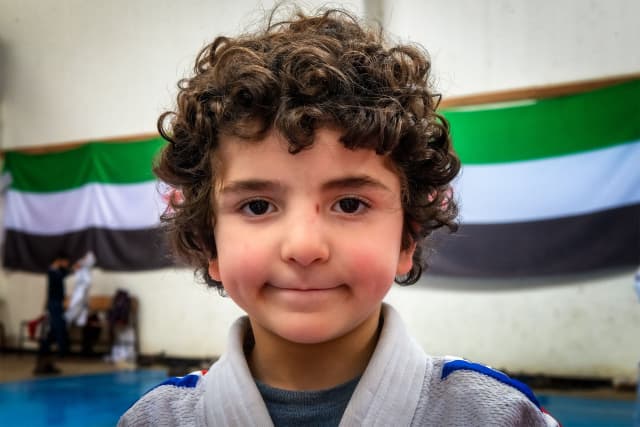

A rich and challenging range of emotions accompanied Leandra and Nicolas throughout the day. Stress is an understandable response, both mental and physiological, but there was also excitement and the need to manage the paradox of feeling true happiness when the laughter and joy of the children having fun on the tatami filled the atmosphere. To be in such a desolate and frightening place, where the absence of humanity is loud and constant, shouldn’t give way to what might seem a trivial happiness, but that is what happens when a glimpse of humanity re-emerges, whether encouraged by judo or by other means.

Many questions ran through Leandra's head, "Being a woman brought even more questions to my mind. Then in the morning, the local people told us it was time to go, in a big van with tinted windows. An armed patrol accompanied us on the way to Syria. We were told that our van could not and would not be stopped until its final destination. When we arrived at the dojo and I stepped inside, I saw all those children in judogi waiting for us and I just wanted to jump on the tatami and teach, to play with them, give them time to smile and show that they are important; as important as any human being on the planet!

Shy and curious looks appeared on all the faces. When the coach asked the children to show the techniques they knew, Nico and I were astonished. What an incredible body shape; some were so small but they could already perform tai-otoshi better than me. They wanted to impress us and they did!"

Ten years ago, before the war started, this Syrian countryside undoubtedly resembled any Middle Eastern countryside, with the wind dancing through olive and almond trees, but after a decade of war, hundreds of thousands of refugees have embedded their shadows here and now live in makeshift camps. Strings of filthy tents are scattered along the road. There are hundreds of disabled residents too and Leandra and Nicolas could see the limping gait of some of them, with no way to offer support or hope.

After the first judo session the delegation continued with their schedule and Nicolas was confronted with some challenging issues, "I realised that the anxiety had not really left me, but that it had turned into acceptance and only decreased gradually with the development of trust in our hosts. It’s a necessarily fragile trust in a landscape where too many values have been trampled upon and crushed by bombs. In this dark picture that continued to form in front of me, without break or respite, the only glimmer of hope I could find was the temporary distraction of seeing children whose traumas are embossed on their skin, finally being children again and being able to behave as such: time for a judo session. For precious minutes they could forget where they were and what they had been through, to focus on the joy of being together and sharing a fleeting normality and the excitement that comes with new things, new people, new experiences."

It’s not unreasonable to accept that most of us can’t relate to the reality people from war-ravaged regions have to endure. We are separated, shielded by social media, by our own lives and the unwillingness to feel all that comes with the knowledge of what these people live and die through. To allow ourselves to view it in all its technicolour horror, is to make ourselves vulnerable and put our own stability at risk. But sometimes we must and sometimes we have to reflect on it enough to know that whenever we have the chance we must make every effort to do the right thing and to behave in the most human way possible.

Leandra explains, “We are talking about children and adults who are living through the war, bombs falling on them at home, gunshots killing their families; violence instead of education was what they had. How do they not run away, but also, how can they? Can you imagine turning your back, leaving behind your house, everything you've built? These people did it and it was that or a likely death.

Then we started the judo class and it was amazing. For more than one hour we saw children and coaches on the tatami, having fun and all hungry to learn. Animated parents, adults on the edge of the tatami, all super concentrated and smiling, finding what was happening in the dojo was really cool. Even our security guards with the big guns were fascinated. Inclusion, gender equity, peace, respect, friendship, all of that was present and visible, even tangible. If there was ever a group of people who felt the power and weight of the phrase 'judo, more than sport,’ it was there in Syria."

Emotions were drawn out to their limits. It’s hard to comprehend just how deeply affected we can be, as comfortable European citizens, when unaccustomed to the extreme survival mentality of people under such pressures.

"On the way to the second dojo, we were very emotional, as we tried to process the poverty, hunger, emptiness. That's what I saw on the faces of the people, as they lived with their refugee population increasing from 40,000 to 700,000 people, because of the war. Even the faces of the officers and security guards looked tired.

Thinking about the second dojo, I don't even know if it can be called a building or even a room, but for those children and their judo teacher it was everything. It is a designated space to set goals, to improve themselves, to escape the outside for a few hours. It is hope, a purpose and a programme with which to scaffold part of their lives.”

For Nicolas, it is certain that to come to do judo here, in this lost and forgotten part of the world, can seem surprising, but one of the many things all the Syrian people need is lightness, jovial moments free from worry. “During two judo sessions, they put on their judogi, the same one that allows all of us to push limits and open so many doors. By doing this we shared a moment of pure happiness with dozens of young judoka, but also with their parents and their teachers. The sweat which collected on their foreheads was the most beautiful of the gifts, as it was not their response to stress or fear, but a product of hard work, motivation, sharing and peace. This is unusual here and it’s special.

One has to have seen what is happening on that side of the border, one has to have felt all the traumas, induced by years of barbarism, to understand the extent to which sport is so important, if we don’t want the world to fall into darkness.”

Leandra agreed on every level, "They were so happy when we stepped inside the second dojo. We almost didn't have a place to move because it was so tiny and at the door everyone was pushing to see what was happening. I just stood there, in the middle of them and we did judo together. It made me believe that there is hope and judo is at least bringing some peace of mind and some joy to the lives of people who are just like me, but for the circumstances of war!”

The time to leave came too fast. It was made very clear to the delegation that they needed to leave Syria before mid-afternoon, because after that time the area always becomes more dangerous.

Leandra recounted more, “On the way back I was so tired but still looking through the windows and wondering why they can’t have the same chances I had. Why can’t those children have an education and dreams? I believe that we can do much more! You know, when a woman carries her baby for 9 months and then the family has to teach the child and show them the world, somehow it feels like we have to do that here. I believe that with the Syrian people it is the same. We need to carry them and show them again how beautiful the world can be if, for a little while, we take care of them and nurture a rebuild. It’s idealistic but it’s how I feel after being here. We must all be together, united in the cause to build a better society and include the people who have been hit so hard by this war.

For Nicolas the conclusion was almost the same, "We shared so many amazing moments shared with the people here. It will take me days to digest everything and locate my ‘parachute.’ In just a matter of hours, we managed to cultivate confidence, to instill it, leaving only positives from the visit. It is not this stay that will solve problems, ones that are beyond us completely, but we have been talking about hope and happiness and here that is beyond what we could expect or imagine. Despite the expectation, we found some and created more.”

Together with Leandra and Nicolas were representatives of the Turkish Judo Federation and of the local Kilis authorities. In the years to come there is a lot of work to do to bring more joy and more hope and to restore faith in the values of a more just human condition. Judo, though it may not be the answer, is without a doubt a worthwhile contribution and one which leaves a lasting mark of positivity. That is something to be proud of.