Marie-Paule is one of those children of judo, who, for family reasons, found themselves crawling on a tatami well before knowing how to walk, “I started doing judo in my mother's womb. My parents were judo teachers. In 1949, dad had created the Strasbourg Judo Club, while mum gave her first lessons from 1955. I was predestined."

However, Marie-Paule's first passion was music and she also liked dance and gymnastics, “I dreamed of becoming a musician. I started with the flute before moving towards the harp. I really wanted to devote my life to it. I did six years at a music conservatory. It was a real passion. Judo did not give me the same emotions at the beginning. I did not think of competing, or in any case, it was was certainly not an end for me. I know that some young people dream of becoming a champion very early on, but this was not my case. It's funny to see today that, from a musician, I became a judo teacher."

From the age of twelve, she started giving judo lessons in her parents' club and then passed a baccalaureate in secretarial skills, "I really liked this subject and I imagined that there was a lot I could do to help others with that.” At the same time, she passed the judo teacher State Certificate and started to compete. “Very quickly I started to win everything, but it did not make me shake with nerves. I went to competitions very relaxed, without the slightest pressure and it worked very well. I was obviously happy to win, but I took it all as a game and I already felt that judo should not be limited to only the medal hunt."

At sixteen, the young woman finished second in her first senior French National Championships and then third the following year. This opened the doors to the national training centre in Paris (INSEP). However, she was not accepted as an intern, “It was not easy; I arrived in the capital without the slightest experience. Very quickly, there was the qualifying tournament in Strasbourg. In my city, I easily won. As I was not an intern at INSEP, that was not enough and another selection was organised. I again won everything by ippon and I got my ticket for the first women's world championships in the history of judo."

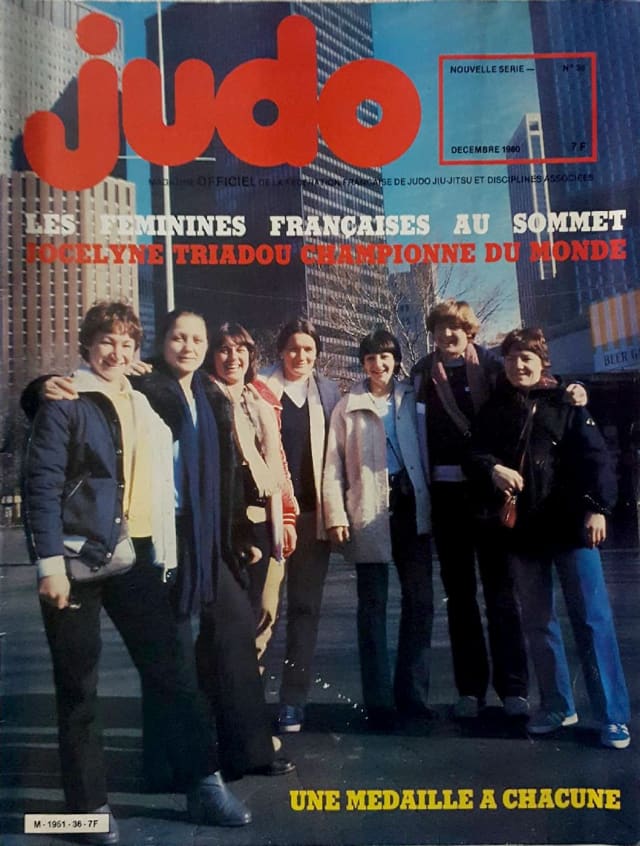

Her performances allowed her, after only a few weeks spent in Paris, to integrate into the national centre and at the end of November of the same year, she flew to New York, “That I will remember all my life; the arrival at night in the city. It was absolutely magical. How beautiful it was," she continues with a tremolo in her voice, before adding, "I had a hard time sleeping. I was so excited to be there. We got there as the Thanksgiving celebrations were in full swing. There were parades in the streets. I was like a child and actually I suppose I was a child, in a way. I was only twenty years old and I had no experience of this kind of travel. I went to see a dance show and I remember that the head of our delegation had her bag stolen with all the team money. We were sharing the room and after going to the police she came back late, but frankly I didn't realise what was going on. I was just thinking about the place and the judo, with no pressure. I knew I was going to give my best, but I was going to do it naturally. For me judo was a cat and mouse game, where the cat has to catch the mouse, that's all!”

The competition took place in the famous Madison Square Garden, “I expected a grandiose room, but we were in a smaller venue. It was nonetheless very warm and very well decorated. Everything was a discovery, every nook concealed treasures. I was a bit on the sidelines of the team, but I got along wonderfully with Jacques Le Berre, the national coach. I drank his words."

She, who did not remember anything, quickly remembered the details of each fight, “I started by taking a Brazilian. I scored waza-ari and then I immobilised her for ippon, in less than a minute. In the next round I was facing a Swiss player, taller and more physical than me. I looked for the action-reaction and from a tomoe-nage attempt, I then scored ippon with ko-soto-gake. Then there was this East German athlete, who was a real monster, a 'vacuum cleaner.’ I wasn't ready for this kind of match, but I got through it once again. I was very difficult to throw. It was my strength. In the semifinals I met the Belgian and she was a beast with an incredible physique. I managed with two or three opportunist’s koka scores.”

Finally, Marie-Paule was in the final of the world championships, “Before me there was the Austrian, several times European champion. I stepped on the tatami, telling myself that it was just one more bout, but I did not see anything, nor master anything. I could not find the slightest solution. I raised my right arm to launch an uchi-mata, but she went under it with her shoulder movement close to the ground, then ended up on the ground. In two steps, three movements, she was on top of me, ready to practise a choke. I got up, but the referee did not say 'matte,’ it was too late! She was definitely stronger than me."

This defeat still holds bad memories for Marie-Paule today and tears are not far away when she mentions it, “It was hard. I was terribly sad not to have won, but looking back, I believe that it all opened up new horizons for me. Maybe if I had won I would have stopped there, when in fact I had learned a lot about the areas in which I still had to improve, tactically, physically and technically. I started to train harder and very quickly, I was nicknamed Ramborette.”

However, the following year, she suffered a serious knee injury and even if she remained a pillar of the French team, she was often a substitute during major events, “It hurt me. It was not easy to accept, but I think that without realising it I was building my future as a judoka. I still couldn't quite make the connection with my future, but I am convinced that this is where my life took a turn. I needed to transmit."

At INSEP, the now world silver medalist quickly passed a literary baccalaureate, then began studying physiotherapy, “I had real support. It built my whole future, but there was the frustration of not being selected for the major competitions and in 1986 I decided to quit and returned to Strasbourg."

As the fire crackles in the stove, she readily admits that at the inaugural New York World Championships, she still didn't quite realise what it was, “I was really young. I know I enjoyed working in a group and was happy to be able to give 100%. I remember memorable physical preparation sessions with Jean-Luc Rougé. We were real guinea pigs, but it was exciting. At the same time, we were hearing taunts from some and remarks from others like 'how come you girls do judo?’ We didn't have the same equipment as the boys. To go to New York we just received a tracksuit. My judogi, I had to patch it myself. It was hard, but I didn't mind living simply, so I didn't have a bad time. I was happy in my own way. It was a beautiful period, one which built me."

Back in Strasbourg, Marie-Paule helped her brother (André Panza - nine times world champion in kickboxing, full-contact and French boxing) to set up his gym. She passed her State Certificate in bodybuilding and helped the development of weightlifting in the region. She settled down, as she explains, “The need to transmit became more and more obvious. I worked in several judo clubs in Alsace. At the same time I worked in a social integration company and also in Germany, where I could apply the principles and values that judo had instilled in me. I then told myself that I was not made to earn money, but to build and transmit. My dream had never been to be a champion. Whether I won or lost, in the end, I was the same person."

Today, she has digested it all and she has of course matured. Now 7th dan in judo, she considers that this does not make her different from others. She is just proud and happy to be able to continue to give judo everything she has received, “The important thing is not the medal, nor the grade, but what you do with it. Coming back to that time in New York, I think if I had realised what was at stake, my life would probably have been very different. I am proud of my career, but I am even more so because of what I did afterwards and especially in my teaching career."

Then she became a coach in the high-level training structure of Strasbourg, which is a springboard towards the national teams. She rubbed shoulders with and trained the new generations. She can now take a step back concerning the development of women's judo, “It remains true even today that it is easier to be called Teddy and to be a man, to have a real sports and media recognition, but things have changed so much. Frankly when I see the Clarisse, Marie-Eve or Madeleine of today, I tell myself that it no longer has much to do with who we were. We were children, when they are wonderful women, full of determination and motivation. They are perfectly prepared and have all the support they need, but I am so proud to have fought to allow today's female champions to be who they are. The way of judo is full of meaning and we have to do everything we can to make it meaningful."

Marie-Paule can now choose to do what she wants according to her abilities and her intentions, “You have to remain coherent, harmonious. I have built myself through my career. When you fight, it's for you. In the end it's not that important to be a world champion. What is, is what you do with it. I admire Lucie Decosse for that. She was an incredible champion. She became an excellent coach. What a great reinvention. Now I have my judo club. I pass on and I dream of setting up courses where I can welcome entire families, in a multi-generational spirit, where everyone can grow by contributing something to the other, so that each one too can find their own inner balance."

She now lives in the countryside, some would say as a hermit, but she denies it, “I am so happy here, far from the hustle and bustle of the city. I am in harmony with myself. I needed to experience what I teach, this harmony of body and mind. My body has suffered. I have undoubtedly asked a little too much, but my mind is able to adapt to it. I live in the heart of nature. For 40 years I was busy with competitions and judo lessons, every night and every weekend. Now I can finally breathe and tell myself that it was all worth it. Human beings are always between Earth and Heaven, not knowing how to take advantage of it. You have to let go. I broke away from it all a bit to grow myself. In all of this life, the New York Championship was an important step, no doubt a crucial one, but it was only one step. I wish all of our today's 'warriors' to one day understand that."

The day is fading away. The fire continues to crackle in the hearth. With her dog at her feet, Marie-Paule is silently remembering the path she has taken. She imagines herself a writer, to put on paper everything she has lived, because she is convinced of it, she still has a lot to transmit.