Only 48 hours ago, thanks to the support of the Kit kad organisation, the local authorities and the Turkish Judo Federation, we were moving from one checkpoint to another, in the middle of the rubble, whether material or human, in landscapes suffocating under the dust.

Finally, 48 hours ago, protected by a cordon of heavily armed special forces, we wandered the streets of Azez and discovered entire families living in tents or in unsanitary accommodation, without water or electricity; families whose children can often no longer go to school because they must work to survive. Indeed, although education is free, going without a monthly income of a few dozen euros, earned by ten year old children, is not an option for millions of refugees.

48 hours later we can finally testify to what we have seen with our own eyes; we can try to understand what drives us when we go to inhuman places that are yet full of humanity like these, but also ask ourselves what we can do to not let it happen.

To this last question, unfortunately, without being too pessimistic, we must recognise that we do not have much power, or even any power at all, to change things. A conflict like the one that has been raging in Syria for a dozen years or like the one that has flooded our media for the last few weeks in Ukraine, is beyond comprehension and above our level of competence or influence.

In 48 hours and a few hours by plane, we went from desolation to opulence, from 'I have nothing' to 'I have everything.’ ‘I have too much,' we should say, from resignation and abandonment of some to excess and the presumptuousness of others.

We are often asked why we go to Syria or Zambia, Malawi, Jordan? Aren't we happy in our comfort zone? If the first question may seem logical and it is, let's be honest, it is totally incongruous to us because we always want to answer, ‘and why not?’ If there are risky acts but these allow us to envisage a better world, then perhaps the risk is worth taking.

On the second question, concerning comfort zones, we are convinced that it is by staying there that we cannot change the world to make it better. Not being afraid to look beyond the horizon is a vital necessity when you still have a notion of what humanity means.

Despite everything, we are aware of the utopia of the approach that animates the ‘Judo for Peace’ programme developed by the International Federation, but if we were not utopians, we would very quickly become defeatist and indifferent to miseries which, let's not forget, even if we believe we are immune to them, are always a potential threat.

The Syrian conflict seems to us, seems to you, perhaps, no doubt, distant. Azez and Mare in Syria or Kilis in Turkey are nevertheless less than four hours by plane from Western Europe.

Thinking about it, we looked at the definition of what peace means. Even if we all have a more or less precise idea, are we able to define a concept accepted by all? It’s not certain because, since time immemorial, peace is undoubtedly what has been most signed by men and the least respected. If we all agreed on a common idea of peace, then we would probably succeed in making it victorious.

Baruch Spinoza said, "Peace is not the absence of war, it is a virtue, a state of mind, a desire for benevolence, trust, justice," and that is what motivates us to take risks, however measured, so that children can smile again, if only for a judo session.

We conceive that there is quite a paradox in saying this, knowing that our discipline is a combat sport, a martial art and that it is the weapon we wield best in order to restore some colour to innocent faces darkened by the crises around the world.

All that is only words, beautiful sentences sprinkled with good conscience, some would say. It is! But they are also acts, gestures and commitments.

Although war is raging, although electricity and running water are only distant memories, a dream, even an unknown territory, since a ten year old child surviving in Azez or Mare has never benefited from either, there is something magical about being on a tatami and practising judo.

Due to the language barrier, there are no more useful words than those exercised when you enter a dojo in Syria. At least those are universal. Nevertheless fraternity, exchange and understanding, there is only that and that is what makes us live.

When, within hours of our return, we received messages such as, “Thank you for your visit, which made our children happy and made their hearts beat faster," or, “We are happy to have welcomed you, the joy of our children was immense," we say to ourselves that our approach has a certain raison d'être.

Yet beyond the pleasure shared at the time, laughter and fleeting happiness, what is all this for? Utopia is good, utility is better. We want to believe that among all these young people we have met, with the hope that arises from our exchanges, they will not fall into the extremes of violence so present and so easy.

We often oppose words and actions, one being a chimera, the other serving to build a good conscience. However, there is a close link between the two and it is because we translate words into deeds that the world evolves.

In the framework of the Judo for Peace programme however, we are inclined to reverse things sometimes. Thus, often everything begins with an act, symbolised by the bow at the beginning and at the end of a judo session, a bow which gradually takes on words imbued with respect, listening and friendship. That's what makes it successful.

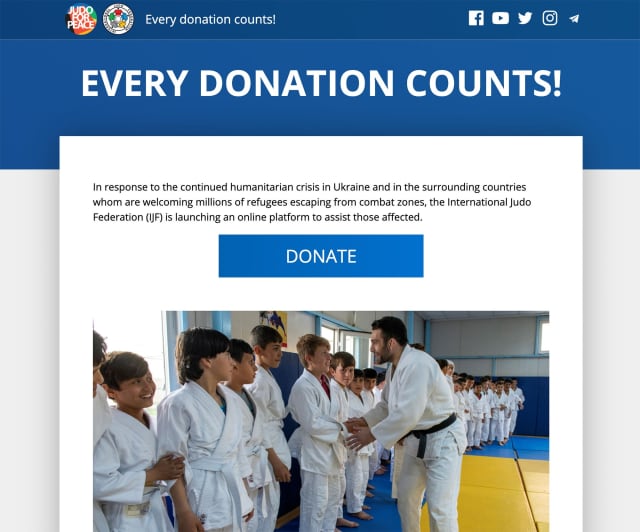

As we speak and to illustrate the concrete activities that have been implemented for many year in different regions of the world, in the countries bordering Ukraine, the International Judo Federation has launched a vast ‘No Borders’ programme with an objective to support the millions of refugees fleeing the war. Two years ago, in Zambia, Malawi and South Africa, we organised a fundraising programme to provide masks as the Covid pandemic raged. During the Tokyo Olympics last summer, a team of refugees competed in the mixed team competition.

https://noborders.ijf.org and https://donation.ijf.org

Also in Tokyo, for the first time there was a match between an Israeli athlete and an unveiled Saudi athlete, in front of cameras from around the world. The two countries have received the Judo for Peace Prize awarded by the International Judo Federation.

In recent years, Judo for Peace actions have been carried out in Canada, within the Inuit community, among the Aborigines of Australia or in the extreme south of Argentina.

We cannot forget the actions we take to preserve our environment. Currently one of our athletes, Sabrina Filzmoser (AUT), is climbing Everest without oxygen. Starting from sea level in India and currently at Everest Base Camp at an altitude of almost 6000m, throughout her journey she has promoted the values of our moral code: politeness, courage, sincerity, honour, modesty, respect, self-control and friendship. We will meet her at the foot of Sagarmatha (Everest) at the end of May, to inaugurate the highest dojo in the world and once again be on the ground, meeting those who benefit so much from development and emphasis, those who need a little extra hope in life.

These are just a few examples of what sport and judo, in this case, allow. If we are proud of the progress achieved, we have no misplaced pride. We are aware that alone we can do nothing, but that it is together that we can go further.

So yes, peace and fraternity are beautiful concepts that become futile and useless if words do not turn into actions and actions do not lead to a respectful speech for everyone's differences.

Yes for peace and fraternity, from words to deeds, but also from deeds to words.