The IJF’s remit in this context is complex but with a firm foundation of values underpinning all that is achieved, the impact is small but wholly positive, against a backdrop of fear, trauma and continued risk. None of it is easy and it is important to remind ourselves, frequently, that what we see on the news and in the sanitised versions of real life stories that are publicised in more glamorous media circles, is often serving to desensitise us. We struggle to allow the emotion of such harrowing human circumstances to touch us and we brush over articles and news reports and videos with almost a shrug.

There is an active war in Syria; we can find the up to date reports and statistics of that on any news channel daily. The migration of thousands upon thousands of families across Europe, seeking safety, is something we have all got used to hearing about. Normal families whom have lost more than just their homes are fleeing almost certain death, finding ways to increase the odds on their children’s fragile survival.

Mums, teachers, refuse collectors, vets, postal workers, nurses, cousins, tiny babies, football coaches, retirees, dancers, lecturers, greengrocers, judoka. Every single person is leaving behind a life just like mine or yours, in an unthinkable effort to just stay alive. Can you close your eyes and think for a moment about you being in that situation. Take a breath in that daydream, in that nightmare. Imagine taking your child’s hand to drag them through those circumstances.

With all that said, we ask that you read this interview carefully, maybe more than once.

On 5th April, following the Antalya Grand Slam, Nicolas Messner and Leandra Freitas traveled through Kilis in Turkey, where Judo for Peace has been working for some time, but with the ultimate aim of crossing the border into Syria. This is not a place the IJF team has accessed before and the logistics involved are complicated and challenging.

Nicolas has traveled extensively and continues to push boundaries in his role as Judo for Peace Director. In no small way, he contributes to important projects that offer judo, judo values, hope and solidarity in an effort to help rebuild devastated communities.

Leandra Freitas, however, is new to this type of work. Leandra is of Portuguese heritage but following her retirement from elite judo she now lives in Hungary. Kilis and Syria were her first experiences of working in refugee camps and it really was jumping in at the deep end. The towns of A'zez and Mare in Syria, formerly bustling communities amid pretty landscapes, have been redesigned by shelling and migration and no longer host market days or school concerts.

This is your first time visiting refugee settlements anywhere. Which of your preconceptions were confirmed or overturned?

“My thoughts about people who run from war, looking for a better life, didn’t change. What we watch on tv is one thing. Hollywood shows us a perception and sometimes these images are made to seem normal. You watch on the news that thousands die in wars like in Syria and people can shrug their shoulders and say ‘ok’ and change the channel. We are conditioned to be more moved by the single death of a pop star or by a tragic car accident, but when thousands die in conflict zones, through no fault of their own, we can somehow just turn away. Movies make this happen. I can’t turn away anymore.

These are women and children and men who all want a good life, just like all of us. They are like me. If tomorrow Hungary gets bombed, my partner will take me and the dog and we will run. It is for survival. I saw the city and it cannot be called a city any more. I was shocked by everything I saw, from the condition of the buildings to the empty looks on people’s faces. My opinion didn’t change, but what I think has been fortified.”

It was also your first time teaching judo in that context. What do you think about the impact of judo for that community and why does it help to have guest visitors to those regions?

“I hope all sports will take up this issue. We have our judo moral code, but really that is a human code, for everyone. What we did, compared to what they need, is nothing, so we need everybody to carry them. They are traumatised and there is no joy. We could see that they are used to not being cared for and it was important for us to show that we were really invested in them. We had that connection and some could see that we really care and that is a big message for people who are used to having no thoughts like that. A one hour class gives an opportunity to show care and hope. It’s not just them saying that they need help. We can now say that they need help. We carry their message.”

Leandra spoke quietly and slowly about what she saw as the response to an hour of judo in those dojos, pointing out that what we see as a tiny gesture is, to those people, an hour of escape from the incessant stress of living in a war zone. For the 60 minutes of a judo class they can focus on their physical health, fun, learning, team work. It’s respite and it’s hope and for some, this fleeting moment is a lifeline.

On the film we can see your emotions right at the surface. Why did you cry?

“How to not cry? Firstly, the whole situation! It’s overwhelming. I’ve seen Roman ruins from the past, romanticised and viewed as a beautiful window to the past, but you know here the ruins are from now. They are the contemporary detritus of unspeakable human suffering. There are bullets in the walls. Such an insecure, continuous situation.

Secondly, because I don’t understand why humans do this to other people. Why does this happen? I think about the children in my family, like my niece. It even came to my mind that my dog had a better standard of living. We cannot compare with any depth of understanding. We are living according to the luck of where we were born. I asked myself a lot of questions. Why can’t these children have a happy childhood? Why are leaders making these choices? The innocent people are being destroyed through no fault of their own. I don’t know how to answer you. It’s bigger than me! It’s important for me that I treat you well and you treat me well. For me we are all the same. Respect between us is so important. When I was there it was important for me to understand that we are all on the same level; we are all the same. I am not more important than them, I was just lucky to be born where I was born.”

What were the most positive moments and why?

“If I bring you 20 children from there they can all be Olympic champion! They’re strong physically, well, of course they are, look at how they live. So it was almost enlightening to see such capability and potential in a place that appears, at first sight, to have no potential at all.

Also, the schools in Syria are separated for boys and girls and it is a strict separation, but for one hour the girls, boys, men are training together. Equality is not a high priority here and ideas of gender equity are very much at the formative stage, but for one hour, when I was leading the class, I could see that they were admiring, not devaluing the experience because I am a woman. It felt like the respect was normal. Later, in conversations with the coaches, I said it would be great to have judo for boys and girls together in schools but they said it’s not possible. They hadn’t realised that the dojo was for everyone and that they had taken part in a mixed judo experience. Everyone mixed naturally. Here women can be married when they are very young and now there is a political movement to change this. Judo, albeit on a small scale, is showing that there are different ways.

Meeting people was the best part. Everything is damaged. Going into the street, there is nothing to see, nothing to appreciate and so the relationships with people become magnified and very important. When communication between people is the only animated facet of life, it becomes everything.

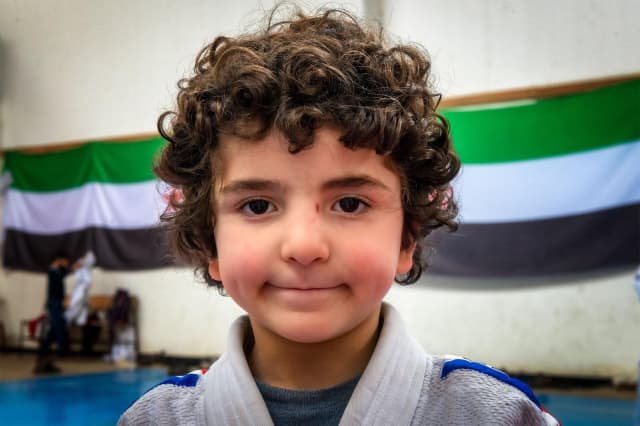

It took me until the end of a session to make one little boy smile. He was around 5 years old, stayed silent the whole time we were there. I tried hard to interact with him and play with him but I saw him retract. He was afraid to have fun, like it was forbidden. He didn’t speak at all, but to have that one half smile from him at the end of our hour, was everything. It illustrated, in its purest form, the power of judo, sport, outreach programmes. It cuts through trauma, not necessarily solving it, but providing much needed vision, escape and hope."

"If I could bring some children home I would. I want to show them that the world is still ok, especially this boy. He’s just a kid!”

What did you feel at the Turkish-Syrian border, on the way in?

“The day before, I was very afraid. I like to have plans and I didn’t really understand anything about how the travel would happen the next day. It seemed that it was a matter of security to not disseminate information, but it made it scary for us. We went in a van, with no notice, with smoky windows. ‘There will be no stops,’ we were told. Everyone had radios and guns. I was shaking on the actual border and I tried to film us crossing but I was so stressed that I didn’t film it properly. I was the only woman in the van and if something happened, for sure it would be bad for me. I felt it very deeply.”

And on the way out?

“Coming out of Syria the checks were more severe. They rushed us out to leave by a certain time. Apparently it was dangerous later and they pushed us out but wouldn’t tell us why. They said that we had to go because eyes can see that we had been there."

"I was so tired from managing the stress and being so alert all the time, processing that everyone had guns and that there were so few women out in the open. We thought we would go back again for a second day but it was not possible, maybe too dangerous, maybe because we had to focus on projects in Kilis too.”

How were the judo values of courage and respect illustrated in the context of the Syrian dojos you visited?

“The people there were the ones really showing what courage and respect is. They put on the judogi and they came together. Just to be there was courageous and to do something so normal as judo. The dojos represented a natural, expected equality which was beautiful, with respect for and from everyone present.”

What did you learn about equality and opportunity?

“I learned that we really need to look, to see honestly what is in front of us. We must fight for the rights of all. I feel that my personal tolerance has changed, many small issues really shouldn’t occupy so much space in our lives. We should always be fighting for our rights but should also be grateful for our homes and jobs and the food on our tables. I always valued it but now, much more.

Gender issues need to be continually noticed too. Everyone has their bad moments and sometimes we have to put ourselves in other people’s skin before making judgements. From an honest overview we can make better decisions about how to move forward and make life better for everyone, really everyone.”

Why should all judoka read these articles and watch these videos?

“Everyone should see this. It is not only a judo context. I don’t know how to help from here at home but individually we can make some small differences. Higher institutions need to make changes too. From the IJF and the Turkish Judo Federation there is a lot of good happening, but all people should read and see that it is a matter of humanity. The way I read the news and read articles from now on will be more careful.

We arrived at a place in our lives where it seems to not concern us, but it really does. Maybe one day it will be us. Compassion is important. Maybe one day we will be fighting for water or to be able to control our temperature, with no way to keep warm in the dark.”

What do you feel now that you had some time to reflect?

“There is not one day that I don’t think about that little boy. His face has stayed with me. Maybe one day I can cross his path again and maybe do more than just visit for an hour of judo. I tried to find out his name and communicate but he didn’t speak even one word. He didn’t talk to anyone. I think there is deep trauma.

Right away I felt that I want to be involved with any positive action there in the future. It’s meaningful. It was my birthday when I came back and I did not do too much but I appreciated that my friends called me and I had flowers from my boyfriend. It was like I appreciated everything so much more, maybe triple. If someone is in a bad mood, maybe just smile at them and they might smile back.

I went for a walk with my dog. I was very aware that I didn’t need someone to walk with me, to protect me. I had a level of freedom that I am now more grateful for.

Even during the training there I was completely enjoying the judo. I tried to take care and do my best, but behave normally. I focussed very closely on our judo and excluded all the guns and the ruins, just for the time on the tatami. In fact, during the judo lessons I can’t remember anything other than that. It’s very noticeable to me that on the mat I was able to block out the horror outside. The fun was more important."

I’m still tired and now I want to turn off my brain. I saw people physically damaged and mentally scarred and now I need to absorb it but not let it haunt my days. It needs to fuel me and allow me to think in the right way about the future and how my roles in judo can contribute.

We all have troubles and have the circumstances in which we live, but we can try to improve their situation a little bit, while we have the opportunity to do so. We have to show them how it is to live again, that there is still joy beyond their geography.”

Listening to Leandra is an emotional exercise. She speaks slowly and very carefully, ensuring she says only honest things, with a total commitment to her respect for the people she met. To visit a place such as A'zez or Mare in Syria, is to open yourself to the most raw and concrete example of what it means to be human, with all its ugliness and all its controls over instinct. It is also a chance to reflect on ones own position and opportunities and to find the most basic routes to happiness, equality and progress.

There are so many layers to this experience that Leandra will have to revisit it many times throughout her life, metaphorically, analysing what it implies for the direction of humanitarian sports projects, absorbing the impact on her assessment of her own life and circumstances, feeding back into work and personal choices. It was so much more than a couple of hours of judo.

Take the time to read and re-read and to be vulnerable to the honesty of Leandra’s accounts. It impacts us all! We can’t live in that reality for long as it is too painful, but we owe it to humanity to at least understand that this life is not simple and is not based on our war-free expectations for everyone.

Applying judo values in Syria and in Leandra’s Hungary and in Nico’s France, can unite us. It’s a common thread that ties us and makes it inevitable that the judo family will continue to provide these pockets of hope.