IJF: You had a dream to go to the Olympics. It's now going to be your fourth participation but today you are almost happier for someone else’s participation than for yours. Tell us why having the possibility for Ngawang Namgyel to participate in Tokyo 2020 makes you over-the-moon happy?

Sabrina Filzmoser: Although it does sound great to have a fourth Olympic qualification in my pocket, it has been such a challenging time with an overwhelming amount of injuries and consequent insecurities, to the point that I nearly didn’t make it. So, as a result, I tried to focus on my development work for Nepal and Bhutan.

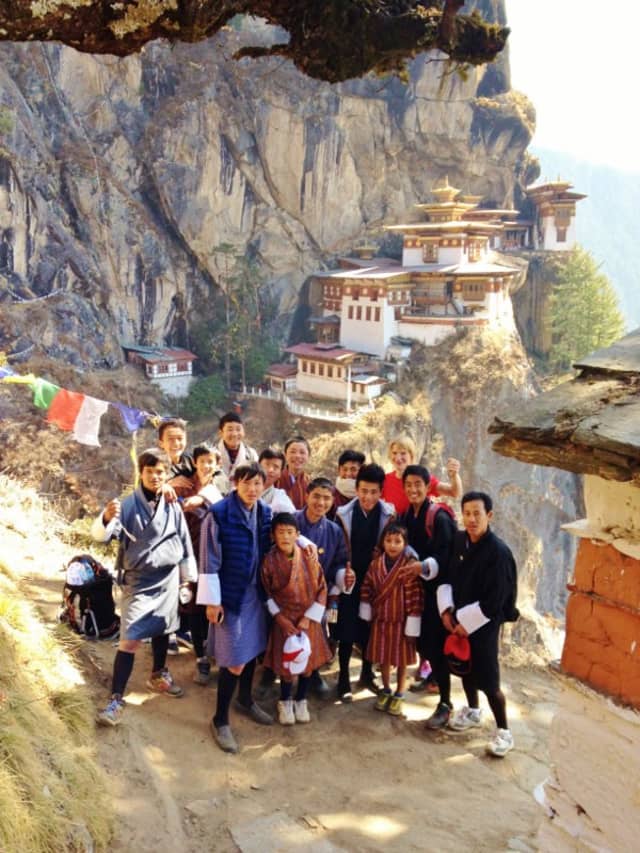

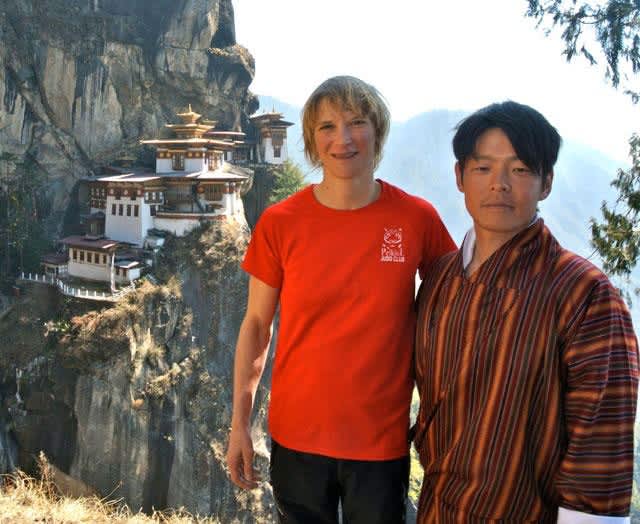

I shared my Olympic dreams and visions with the young Bhutanese judoka after my London 2012 experience, so from there on I’ve had a strong connection with them. Ngawang has always been a humble and strong competitor and he so deserves his nomination for Tokyo.

IJF: It's been years that you've been involved in the Himalayas, especially in Nepal and Bhutan. You went to Bhutan for the first time in 2012 after London. Why there? Why do you believe that judo can be of benefit there?

Sabrina: After my 7th place in London I was extremely sad and disappointed but couldn’t exactly explain why, because I had given everything possible during that time. During the closing ceremony I met the Bhutanese team, as they were standing right next to our Austrian delegation. I had heard a lot about this small mountainous Himalayan kingdom squeezed between the big neighbouring countries of India, China and Nepal.

The Bhutanese delegation included archer Sherab Zam and shooter Kunzang Choden. Zam was the flag bearer for both the opening and the closing ceremonies but what was really impressive was that Bhutan was a country which had a female-only team at those Games.

I spoke to them and found out that the reason they knew about judo was because, at Pelkhil school in Thimpu, judo was already taught at a very early age to some children.

This goes back to principal Karma, who is married to his Japanese wife Rie and they both wanted their children to get the chance to be educated according to Jigoro Kano’s philosophy. All of the judo ethics and values are being taught to the already very humble and respectful Bhutanese and it very much reflects their traditional life, full of humility.

IJF: Could you tell us more about your involvement in Bhutan? How did it start? How does it work? When do you go there? What do you do?

Sabrina: From the very beginning, I tried to support them by sharing my values, thoughts and Olympic vision. Prior to my first trip to Bhutan, which was shortly after the Games in London, I put together nearly 300kg of judogi and sports equipment for various sport groups, ranging from judoka to mountain bikers.

It’s actually really difficult to enter Bhutan as they have very strict visa restrictions but because of my work for the Olympic committee I had the chance to take part in the toughest one day Himalayan mountain bike race called ‘Tour of the Dragon.’ Racing over numerous high altitude passes, lasting 254km, through heavy rain, terrible mud terrain with freezing temperatures, somehow, I survived and won the race! The reward was pure joy; I felt overwhelmed, really happy.

Bhutan is known for its innovative Gross National Happiness (GNH) development policy that prioritises the wellbeing of its people. In Bhutan, GNH is more important than Gross National Product (GNP). From there on I promised to organise support and to send or bring equipment to this absolutely stunning, awesome place. I had worked and helped to get Bhutan recognised by our judo community and soon they became a full member of the International Judo Federation.

IJF: Who is supporting you and what are your goals? What do you think can be achieved?

Sabrina: There are a great number of wonderful people, not only in Japan but around the world, who support and help to realise my Himalayan development dreams but the most valuable people to me are Karma and Rie; they founded Bhutan Judo by themselves. They had an amazing vision and figured out how to organise and teach high quality judo skills via the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) and they had Japanese judo coaches right from the beginning. I remember those times very well, when we spoke about getting one young Bhutanese judoka to the Olympics, maybe to Tokyo; that was in 2013! So there’s so much to dream about and work on for the future.

Also worth mentioning is that the Japanese embassy helped to finance the construction of a new dojo, which has been so difficult to realise during the pandemic, involving incredibly long delays, but it will be opened this year. The company Seisa Group Japan gave two young talented Bhutanese judoka, Tandin Wangchuk and Kinley Tshering, a scholarship to study and train at a university in Hokkaido.

IJF: The participation of Ngawang Namgyel will be absolutely amazing. What do you want to tell him about the Games, based on your incredible experience? What do you think this participation can do to help develop judo further in the country?

Sabrina: I told him already that he should not put too much pressure on himself. Yes, the whole country will follow his participation and yes, everyone will be so proud of him but he should just be himself: a humble and respectful athlete giving everything until the end. It’s of much greater importance that he should truly enjoy each second before, during and after the Games, because for him it will quite possibly be a once in a lifetime experience.

Yes, of course the future could hold so much more for him than that. Once he secures a potential scholarship to study and train in Japan or maybe even undertake some education as a coach, he would then come back and teach the same high values he was taught in Japan. And so the circle is complete! The wonderful circle of education; it’s like an obsession, once you have experienced it, how this passion of judo can spread.

IJF: You have also been working hand in hand with Nepal and in Rio Phupu Lamu Khatri participated in the Games. It should also be the case for another Nepalese athlete this year in Tokyo. This is about top level sport but in that region of the world it's about education as well and that's where judo can be of great help.

Sabrina: Absolutely, like I mentioned before: once you dare to dream, your goals can be realised in a totally different manner. It is not about setting those aims and goals, no, it is actually tough daily work in order to reach them but people living in this region know how to work hard every single day. They know how to survive. They had to learn that because they had to find out how to dig out the potatoes from the hard frozen soil. It’s definitely like that saying, ‘you first have to sew before you will be able to harvest.’

Soniya Bhatta, -48kg from Nepal, received an IOC wildcard; it’s a huge achievement for the Nepalese Judo Federation. In Rio 2016, Phupu Lhamu Khatri was able to make the entire nation proud by being a Sherpa girl bearing the flag in the Maracana Stadium. Her father, a very well known, famous Sherpa, died during the devastating avalanche at the Khumbu Icefall on Everest, where 22 Sherpas lost their lives. Without any kind of insurance back then the families lost everything.

IJF: Being a top level athlete for so many years and being involved in development activities and now also being the chair of the IJF Athletes' Commission gives you unarguable legitimacy. How do you want to use that platform?

Sabrina: From my experienced, high quality education is, I believe, the perfect path to bridge the gap between different cultures and to reconcile various civilisations. Without the right to proper education, the values of liberty, justice and equality can have no meaning. Ignorance is by far the biggest danger and threat to humanity.

My overarching goal is to further support athletes, no matter their age, gender, religion, tradition or nationality, by outlining a common set of aspirational rights and responsibilities. Every athlete should be able to cover topics such as anti-doping, integrity, clean sport, career, communications, governance, discrimination, due process and protection from harassment and abuse.

IJF: Tell us also a little bit about you. Your fourth Games; this is impressive and not so many athletes, across all sports, can say they went to four Olympic Games, especially after the pandemic that postponed Tokyo 2020. How do you feel? How hard was it and how hard is it still?

Sabrina: For sure my highest goal has always been to reach a life-long goal of winning an Olympic medal. Striving for it, coming back from numerous injuries and setbacks, has made it a bumpy and rocky road, even with all the incredible effort I put into it but one day I heard the words of a very good friend who had already reached that enormously high goal, “You could be absolutely happy with an Olympic medal, but it could also feel useless and sad a while afterwards."

Somehow I was shocked and I wanted for myself that this would never happen to me. Whenever something did not go as planned, I always felt happy to be able to make the best out of each disappointing situation, especially during the pandemic. I had the idea of establishing a ‘Gofundme’ project to collect metres of altitude by climbing, biking and mountaineering as high as Mt. Everest (8848m) to support my Everest Judo programme in Nepal. To me it felt like I could work on my stamina and endurance ‘usefully’ for several weeks and months, collecting more than 200,000 metres in the process. This would never have been possible without the pandemic! Full of gratitude, I realised so many of my friends around the world followed and helped to support this project.

IJF: As someone always with a goal in life, you must have other/new objectives? Where do you want to be next and how do you imagine using judo as a development tool?

Sabrina: There are several visions for sure, because I have always had not only a plan B, but also a plan C, D, E, F and beyond. Sometimes I encounter noticeable disapproval from people who question my choices, even my closest friends and family. They don’t understand why I do certain things, questioning my logic. They challenge my sanity and even call me crazy. They say I can’t do whatever I am about to endeavour to do but over time I have come to realise that even though I face a little bit of opposition at times, most of the ‘they’ who criticise me really only exist in my head. So, somehow I feel violated by my own ambition, for example, the daring plan to go on a no-bottled oxygen climb up to Everest, starting from sea level. It’s all mentally challenging.

Judo has helped me a lot, to develop, to improve day by day. To sum it all up, I want to use all my experiences in high level sport, my technical engineering education, my scientific skills, my education as a commercial pilot and turn it into something even more challenging. I already went to the next step and sent my application to become a European Space Agency astronaut. So that would be a task which could possibly take up the next few months and years, but we’ll see. I have to take one step after the other and eventually be better than more than 22,000 other applicants.

IJF: You’ve been very close to the Judo for Peace philosophy. What do you think about it? How do you think a so-called combat sport can become a peace-building development tool? What makes judo so different?

Sabrina: Our judo philosophy is very different because it builds peace wherever you train and fight together on a tatami. You’ll only be able to feel it when you enter and share this unique mentality. I am completely convinced that a great athlete is one who takes advantage of the potential that genetics gave him or her, in order to care for great achievements but an exceptional athlete is one who can swim in the waters of complexity and chaos, making what seems so difficult very easy, creating order from that very chaos. Creative individuals search for chaos in order to explore all the extraordinary places they can imagine, beyond the frontiers of consciousness, following the irrational forces that come from within themselves and from their environment. That’s peace.

IJF: Tokyo 2020 is just around the corner. How do you feel about going to Japan and about judo being back in Japan?

Sabrina: I’m immensely proud and somehow overwhelmed to be able to actually experience it soon. Although I have so far been unable to reach my lifelong dream of an Olympic medal but now being qualified for these special Games in the very country where judo was born and where I spent nearly fifty training camps for weeks and months at a time over the last 25 years, feels incredibly special.

The Japanese fighters, their judo community, their philosophy and their life lessons have taught me to overcome so many difficulties. I really learnt that if I commit to something, I will have to commit 100 percent. There's no reason to hold back. I will be there using all my might and doing it half-heartedly could only trip me up and make the experience dangerous.

IJF: You are also an IJF climate ambassador. This must be connected with everything we said so far. How do you see that connection with the global framework of your activities?

Sabrina: I really enjoy being able to act and do something to make a change. I really love to support the IJF Climate Champion actions, including support with cleaning areas where tourists don’t care about the trash they leave behind, especially in high altitude areas. We should be carers and keepers of our sacred mountain environments and communities, ensuring that all future generations are able to enjoy and thrive within them, because we all have a duty to fight for our fragile environment on this planet. There are no, or rather, should be no free passengers on this spaceship called Earth. We are all crew members and must care for it together.

IJF: Do you have a message for Bhutan, Nepal and the world, for the next generation?

Sabrina: We gain the most experience when we fail. Failure in itself is not tragic. The question is how does one deal with the experience of failure? What follows immediately afterwards, the inner effect, the questioning of the ego, including despair, is the key to this. Failure is a new beginning and the opportunity to experience your limits and grow even with your doubts. My inner attitude has changed, especially due to my frequent failures. I did not get any softer in the process, only tougher. Failure teaches us to reassess our limitations, giving rise to new ones, ones that we can again leap over in the future as we push ourselves towards greater challenges.