Argentina is a cultured country, probably the most European in South America. It is also a sports powerhouse. Although today it is a nation proud of the Olympic title won by Paula Pareto in 2016, forty years ago things were different and national pride ran in other directions.

"We were freaks," says Rosa. She is the oldest of the three. “Judo was not very widespread, much less among women.”

They go straight to the point and answer bluntly. "At first I took it as an indispensable tool to learn to defend myself," explains Norma. "Then it turned into passion."

The passion of a life, the healthy method to face the complexities of teenage girl’s life, the weight, the appearance, the look of the others. Judo was a total therapy to get ahead with a healthy body and a strong mind.

"It was a discovery," says Stella, "because we were never afraid or ashamed again and we practised it without giving up our feminine condition."

Rosa took care of Stella. They are six years apart and in sports, six years is a world away, even more so when a special event is looming on the horizon. The word historic is used a lot, often without meaning or assigning hierarchy to anodyne things. However, a first world championship for women in a context of sociological change, at a time when women claimed their rights and status, deserves, without a doubt, the label of being historic.

However, in sport as elsewhere, there are categories. The 1980 Argentine team consisted of seven athletes, a lot of enthusiasm and no help. "As we had no resources, we had to pay for the trip, the tickets, the food, everything," says Rosa. It has merit and this is important for those who want to understand what a passion for judo means and the inherent values of this discipline, especially when there is a material shortage.

These young women, some teenagers, wanted to be protagonists and witnesses. As Argentina was not exactly on the side of the United States and there was a shortage of budget, we can already sketch a picture of the moral strength of these pioneers.

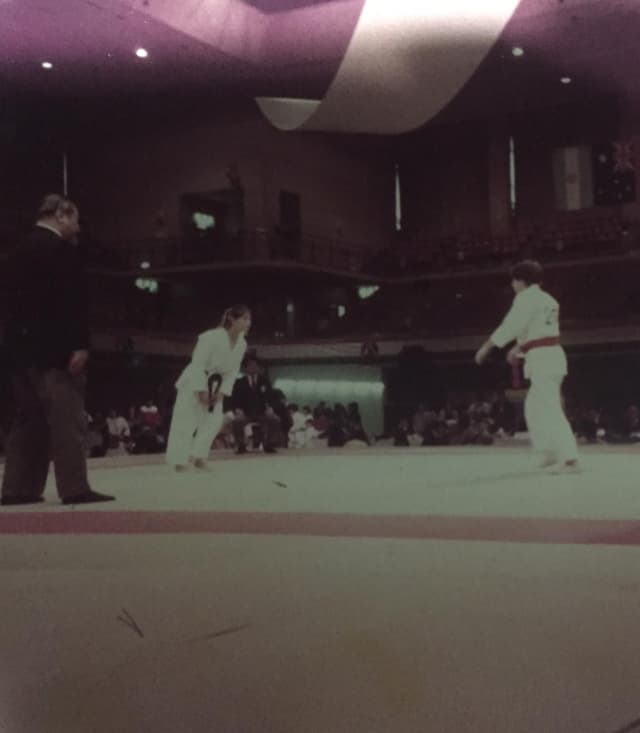

Thus, they arrived in New York and faced the unknown. Rosa, in the -52kg category, lost both of her contests. Stella, at 68kg, the same thing happened. "They were heavier, stronger."

Norma set the bar very high because she was fifteen years old. She couldn't vote, drive or drink alcohol at that time, but she could fight the best in the world. And so she fought, with her guts, with that typical Argentine determination. As we talk about history, Norma competed for the bronze medal and ended up being the highest ranked Latin American judoka. She tells us all this with great satisfaction, but without arrogance. There is a difference, it is what judo brings.

It's hard to imagine the whirlwind of sensations experienced in just a few days. A first trip to New York, a first world championship, a war to obtain recognition from the most conservative sectors and all this while being very young, that is, with hardly any breadth of life experience.

"Judo gave us security and humility," says Rosa. "Loyalty and respect," adds Norma. "Passion and conviviality,” concludes Stella.

Norma retired in 1987. "Before retirement I took revenge in the 1983 world championship against the French woman who had defeated me in New York." Because, why deny it, New York was a precious event due to its symbolic charge, but at the sporting level, it had left pending accounts.

Back in Buenos Aires, Stella moved a hundred and twenty kilometres from her dojo. There she married, had two children and founded a new home. She works as a merchant and moved away from judo, but says she misses it very much. With a mischievous smile she adds, "although my son started doing judo because he wanted to connect with me and get to know me better."

As for Rosa, she kept practising and teaching in different places until she got pregnant. She had to give up practice, but not theory because she has many friends all over the world, so many of them judoka.

They are three flowers, Rosa González Feilberg, Stella Maris Bicchieri and Norma Casco; three forces of nature. Seeing and talking to them, even through a screen, so smiley, so proud of their journeys and so kind and polite, makes us understand that they breathe judo through all their pores and live their lives based on values forged when they were young people and everything was adversity. At this point we assume that the will of these golden girls has already completely melted the Perito Moreno.